Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway | |

|---|---|

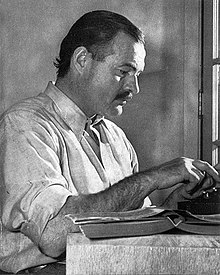

Hemingway in 1939 | |

| Born | July 21, 1899 Oak Park, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | July 2, 1961 (aged 61) Ketchum, Idaho, U.S. |

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouses | |

| Children | |

| Signature | |

Ernest Miller Hemingway (/ˈhɛmɪŋweɪ/ HEM-ing-way; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized for his adventurous lifestyle and outspoken, blunt public image. Some of his seven novels, six short-story collections and two non-fiction works have become classics of American literature, and he was awarded the 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature.

Hemingway was raised in Oak Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. After high school, he spent six months as a reporter for The Kansas City Star before enlisting in the Red Cross. He served as an ambulance driver on the Italian Front in World War I and was seriously wounded by shrapnel in 1918. In 1921, Hemingway moved to Paris, where he worked as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star and was influenced by the modernist writers and artists of the "Lost Generation" expatriate community. His debut novel, The Sun Also Rises, was published in 1926. In 1928, Hemingway returned to the U.S., where he settled in Key West, Florida. His experiences during the war supplied material for his 1929 novel A Farewell to Arms.

In 1937, Hemingway went to Spain to cover the Spanish Civil War, which formed the basis for his 1940 novel For Whom the Bell Tolls, written in Havana, Cuba. During World War II, Hemingway was present with Allied troops as a journalist at the Normandy landings and the liberation of Paris. In 1952, his novel The Old Man and the Sea was published to considerable acclaim, and won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. On a 1954 trip to Africa, Hemingway was seriously injured in two successive plane crashes, leaving him in pain and ill health for much of the rest of his life. He died by suicide at his house in Ketchum, Idaho, in 1961.

Early life

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born on July 21, 1899, in Oak Park, Illinois, an affluent suburb just west of Chicago,[1] to Clarence Edmonds Hemingway, a physician, and Grace Hall Hemingway, a musician. His parents were well-educated and well-respected in Oak Park,[2] a conservative community about which resident Frank Lloyd Wright said, "So many churches for so many good people to go to."[3] When Clarence and Grace Hemingway married in 1896, they lived with Grace's father, Ernest Miller Hall,[4] after whom they named their first son, the second of their six children.[2] His sister Marcelline preceded him in 1898, and his younger siblings included Ursula in 1902, Madelaine in 1904, Carol in 1911, and Leicester in 1915.[2] Grace followed the Victorian convention of not differentiating children's clothing by gender. With only a year separating the two, Ernest and Marcelline resembled one another strongly. Grace wanted them to appear as twins, so in Ernest's first three years she kept his hair long and dressed both children in similarly frilly feminine clothing.[5]

Grace Hemingway was a well-known local musician,[6] and taught her reluctant son to play the cello. Later he said music lessons contributed to his writing style, as evidenced in the "contrapuntal structure" of For Whom the Bell Tolls.[7] As an adult Hemingway professed to hate his mother, although they shared similar enthusiastic energies.[6] His father taught him woodcraft during the family's summer sojourns at Windemere on Walloon Lake, near Petoskey, Michigan, where Ernest learned to hunt, fish and camp in the woods and lakes of Northern Michigan. These early experiences instilled in him a life-long passion for outdoor adventure and living in remote or isolated areas.[8]

Hemingway went to Oak Park and River Forest High School in Oak Park between 1913 and 1917, where he competed in boxing, track and field, water polo, and football. He performed in the school orchestra for two years with his sister Marcelline, and received good grades in English classes.[6] During his last two years at high school he edited the school's newspaper and yearbook (the Trapeze and Tabula); he imitated the language of popular sportswriters and contributed under the pen name Ring Lardner Jr.—a nod to Ring Lardner of the Chicago Tribune whose byline was "Line O'Type".[9] After leaving high school, he went to work for The Kansas City Star as a cub reporter.[9] Although he stayed there only for six months, the Star's style guide, which stated "Use short sentences. Use short first paragraphs. Use vigorous English. Be positive, not negative", became a foundation for his prose.[10]

World War I

Hemingway wanted to go to war and tried to enlist in the U.S. Army but was not accepted because he had poor eyesight.[11] Instead he volunteered to a Red Cross recruitment effort in December 1917 and signed on to be an ambulance driver with the American Red Cross Motor Corps in Italy.[12] In May 1918, he sailed from New York, and arrived in Paris as the city was under bombardment from German artillery.[13] That June he arrived at the Italian Front, holding the ranks of second lieutenant (A.R.C.) and sottotenente (Italian Army) simultaneously.[14] On his first day in Milan, he was sent to the scene of a munitions factory explosion to join rescuers retrieving the shredded remains of female workers. He described the incident in his 1932 non-fiction book Death in the Afternoon: "I remember that after we searched quite thoroughly for the complete dead we collected fragments."[15] A few days later, he was stationed at Fossalta di Piave.[15]

On July 8, right after bringing chocolate and cigarettes from the canteen to the men at the front line, the group came under mortar fire. Hemingway was seriously wounded.[15] Despite his wounds, he assisted Italian soldiers to safety, for which he was decorated with the Italian War Merit Cross (Croce al Merito di Guerra) and with the Italian Silver Medal of Military Valor (Medaglia d'argento al valor militare).[note 1][16][17] For his deed, he saw furthermore promotion to first lieutenant (A.R.C.) and tenente (Italian Army).[18] He was only 18 at the time. Hemingway later said of the incident: "When you go to war as a boy you have a great illusion of immortality. Other people get killed; not you ... Then when you are badly wounded the first time you lose that illusion and you know it can happen to you."[19] He sustained severe shrapnel wounds to both legs, underwent an immediate operation at a distribution center, and spent five days at a field hospital before he was transferred for recuperation to the Red Cross hospital in Milan.[20] He spent six months at the hospital, where he met "Chink" Dorman-Smith. The two formed a strong friendship that lasted for decades.[21]

While recuperating, Hemingway fell in love with Agnes von Kurowsky, a Red Cross nurse seven years his senior. When Hemingway returned to the United States in January 1919, he believed Agnes would join him within months, and the two would marry. Instead, he received a letter from her in March with news that she was engaged to an Italian officer. Biographer Jeffrey Meyers writes Agnes's rejection devastated and scarred the young man; in future relationships Hemingway followed a pattern of abandoning a wife before she abandoned him.[22] His return home in 1919 was a difficult time of readjustment. Before the age of 20, he had gained from the war a maturity that was at odds with living at home without a job and with the need for recuperation.[23] As biographer Michael S. Reynolds explains, "Hemingway could not really tell his parents what he thought when he saw his bloody knee." He was not able to tell them how scared he had been "in another country with surgeons who could not tell him in English if his leg was coming off or not."[24]

That September, he went on a fishing and camping trip with high school friends to the back-country of Michigan's Upper Peninsula.[19] The trip became the inspiration for his short story "Big Two-Hearted River", in which the semi-autobiographical character Nick Adams takes to the country to find solitude after coming home from war.[25] A family friend offered Hemingway a job in Toronto, and with nothing else to do, he accepted. Late that year, he began as a freelancer and staff writer for the Toronto Star Weekly. He returned to Michigan the next June[23] and then moved to Chicago in September 1920 to live with friends, while still filing stories for the Toronto Star.[26] In Chicago, he worked as an associate editor of the monthly journal Cooperative Commonwealth, where he met novelist Sherwood Anderson.[26]

He met Hadley Richardson through his roommate's sister. Later, he claimed, "I knew she was the girl I was going to marry."[27] Red-haired, with a "nurturing instinct", Hadley was eight years older than Hemingway.[27] Despite the age difference, she seemed less mature than usual for a woman her age, probably because of her overprotective mother.[28] Bernice Kert, author of The Hemingway Women, claims Hadley was "evocative" of Agnes, but Agnes lacked Hadley's childishness. After exchanging letters for a few months, Hemingway and Hadley decided to marry and travel to Europe.[27] They wanted to visit Rome, but Sherwood Anderson convinced them to go to Paris instead, writing letters of introduction for the young couple.[29] They were married on September 3, 1921; two months later, Hemingway signed on as a foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star and the couple left for Paris. Of Hemingway's marriage to Hadley, Meyers claims: "With Hadley, Hemingway achieved everything he had hoped for with Agnes: the love of a beautiful woman, a comfortable income, a life in Europe."[30]

Paris

Anderson suggested Paris because it was inexpensive and it was where "the most interesting people in the world" resided. There Hemingway would meet writers such as Gertrude Stein, James Joyce and Ezra Pound who "could help a young writer up the rungs of a career".[29] Hemingway was a "tall, handsome, muscular, broad-shouldered, brown-eyed, rosy-cheeked, square-jawed, soft-voiced young man."[31] He lived with Hadley in a small walk-up at 74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine in the Latin Quarter, and rented a room nearby for work.[29] Stein, who was the bastion of modernism in Paris,[32] became Hemingway's mentor and godmother to his son Jack;[33] she introduced him to the expatriate artists and writers of the Montparnasse Quarter, whom she referred to as the "Lost Generation"—a term Hemingway popularized with the publication of The Sun Also Rises.[34] A regular at Stein's salon, Hemingway met influential painters such as Pablo Picasso, Joan Miró, Juan Gris,[35] and Luis Quintanilla. [36] He eventually withdrew from Stein's influence, and their relationship deteriorated into a literary quarrel that spanned decades.[37]

Pound was older than Hemingway by 14 years when they met by chance in 1922 at Sylvia Beach's bookstore Shakespeare and Company. They visited Italy in 1923 and lived on the same street in 1924.[31] The two forged a strong friendship; in Hemingway Pound recognized and fostered a young talent.[35] Pound—who had just finished editing T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land—introduced Hemingway to the Irish writer James Joyce,[31] with whom Hemingway frequently embarked on "alcoholic sprees".[38]

During his first 20 months in Paris, Hemingway filed 88 stories for the Toronto Star newspaper.[39] He covered the Greco-Turkish War, where he witnessed the burning of Smyrna, and wrote travel pieces such as "Tuna Fishing in Spain" and "Trout Fishing All Across Europe: Spain Has the Best, Then Germany".[40] Almost all his fiction and short stories were lost, when in December 1922 as she was traveling to join him in Geneva, Hadley lost a suitcase filled with his manuscripts at the train station Gare de Lyon. He was devastated and furious.[41] Nine months later the couple returned to Toronto, where their son John Hadley Nicanor was born on October 10, 1923. During their absence, Hemingway's first book, Three Stories and Ten Poems, was published in Paris. All that remained after the loss of the suitcase were two of the stories the volume contained; he wrote the third story early in 1923 while in Italy. A few months later, in our time (without capitals) was produced in Paris. The small volume included 18 vignettes, a dozen of which he wrote the previous summer during his first visit to Spain, where he discovered the thrill of the corrida. He considered Toronto boring, missed Paris, and wanted to return to the life of a writer, rather than live the life of a journalist.[42]

Hemingway, Hadley, and their son (nicknamed Bumby) returned to Paris in January 1924 and moved into an apartment on the rue Notre-Dame des Champs.[42] Hemingway helped Ford Madox Ford edit The Transatlantic Review, which published works by Pound, John Dos Passos, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, and Stein, as well as some of Hemingway's own early stories such as "Indian Camp".[43] When Hemingway's first collection of stories, In Our Time, was published in 1925, the dust jacket bore comments from Ford.[44][45] "Indian Camp" received considerable praise; Ford saw it as an important early story by a young writer,[46] and critics in the United States praised Hemingway for reinvigorating the short-story genre with his crisp style and use of declarative sentences.[47] Six months earlier, Hemingway had met F. Scott Fitzgerald, and the pair formed a friendship of "admiration and hostility".[48] Fitzgerald had published The Great Gatsby the same year: Hemingway read it, liked it, and decided his next work had to be a novel.[49]

The year before, Hemingway visited the Festival of San Fermín in Pamplona, Spain, for the first time, where he became fascinated by bullfighting.[50] The Hemingways returned to Pamplona again in 1924 and a third time in June 1925; that year, they brought with them a group of American and British expatriates: Hemingway's Michigan boyhood friend Bill Smith, Donald Ogden Stewart, Lady Duff Twysden (recently divorced), her lover Pat Guthrie, and Harold Loeb.[51]

A few days after the fiesta ended, on his birthday (July 21), he began to write the draft of what would become The Sun Also Rises, finishing eight weeks later.[52] A few months later, in December 1925, the Hemingways left to spend the winter in Schruns, Austria, where Hemingway began extensively revising the manuscript. Pauline Pfeiffer, the daughter of a wealthy Catholic family in Arkansas, who came to Paris to work for Vogue magazine, joined them in January. Against Hadley's advice, Pfeiffer urged Hemingway to sign a contract with Scribner's. He left Austria for a quick trip to New York to meet with the publishers and, on his return, began an affair with Pfeiffer during a stop in Paris, before returning to Schruns to finish the revisions in March.[53] The manuscript arrived in New York in April; he corrected the final proof in Paris in August 1926, and Scribner's published the novel in October.[52][54][55]

The Sun Also Rises epitomized the post-war expatriate generation,[56] received good reviews and is "recognized as Hemingway's greatest work".[57] Hemingway himself later wrote to his editor Max Perkins that the "point of the book" was not so much about a generation being lost, but that "the earth abideth forever"; he believed the characters in The Sun Also Rises may have been "battered" but were not lost.[58]

Hemingway's marriage to Hadley deteriorated as he was working on The Sun Also Rises.[55] In early 1926, Hadley became aware of his affair with Pfeiffer, who came to Pamplona with them that July.[59][60] On their return to Paris, Hadley asked for a separation; in November she formally requested a divorce. They split their possessions while Hadley accepted Hemingway's offer of the proceeds from The Sun Also Rises.[61] They were divorced in January 1927, and Hemingway married Pfeiffer in May.[62]

Before his marriage to Pfeiffer, Hemingway converted to Catholicism.[63] They honeymooned in Le Grau-du-Roi, where he contracted anthrax, and he planned his next collection of short stories,[64] Men Without Women, which was published in October 1927,[65] and included his boxing story "Fifty Grand". Cosmopolitan magazine editor-in-chief Ray Long praised "Fifty Grand", calling it, "one of the best short stories that ever came to my hands ... the best prize-fight story I ever read ... a remarkable piece of realism."[66]

By the end of the year Pauline was pregnant and wanted to move back to America. Dos Passos recommended Key West, and they left Paris in March 1928. Hemingway suffered a severe head injury in their Paris bathroom when he pulled a skylight down on his head thinking he was pulling on a toilet chain. This left him with a prominent forehead scar, which he carried for the rest of his life. When Hemingway was asked about the scar, he was reluctant to answer.[67] After his departure from Paris, Hemingway "never again lived in a big city".[68]

Key West

Hemingway and Pauline went to Kansas City, Missouri, where their son Patrick was born on June 28, 1928, at Bell Memorial Hospital.[69] Pauline had a difficult delivery; Hemingway wrote a fictionalized version of the event in A Farewell to Arms. After Patrick's birth, they traveled to Wyoming, Massachusetts, and New York.[70] On December 6, Hemingway was in New York visiting Bumby, about to board a train to Florida, when he received the news that his father Clarence had killed himself.[note 2][71] Hemingway was devastated, having earlier written to his father telling him not to worry about financial difficulties; the letter arrived minutes after the suicide. He realized how Hadley must have felt after her own father's suicide in 1903, and said, "I'll probably go the same way."[72]

Upon his return to Key West in December, Hemingway worked on the draft of A Farewell to Arms before leaving for France in January. He had finished it the previous August but delayed the revision. The serialization in Scribner's Magazine was scheduled to appear in May. In April, he was still working on the ending, which he may have rewritten as many as seventeen times. The completed novel was published on September 27, 1929.[73] Biographer James Mellow believes A Farewell to Arms established Hemingway's stature as a major American writer and displayed a level of complexity not apparent in The Sun Also Rises.[74] In Spain in mid-1929, Hemingway researched his next work, Death in the Afternoon. He wanted to write a comprehensive treatise on bullfighting, explaining the toreros and corridas complete with glossaries and appendices, because he believed bullfighting was "of great tragic interest, being literally of life and death."[75]

During the early 1930s, Hemingway spent his winters in Key West and summers in Wyoming, where he found "the most beautiful country he had seen in the American West" and hunted deer, elk, and grizzly bear.[76] He was joined there by Dos Passos. In November 1930, after taking Dos Passos to the train station in Billings, Montana, Hemingway broke his arm in a car accident. He was hospitalized for seven weeks, with Pauline tending to him. The nerves in his writing hand took as long as a year to heal, during which time he suffered intense pain.[77]

His third child, Gloria Hemingway, was born a year later on November 12, 1931, in Kansas City as "Gregory Hancock Hemingway".[note 3][78] Pauline's uncle bought the couple a house in Key West with a carriage house, the second floor of which was converted into a writing studio.[79] He invited friends—including Waldo Peirce, Dos Passos, and Max Perkins[80]—to join him on fishing trips and on an all-male expedition to the Dry Tortugas. He continued to travel to Europe and to Cuba, and—although in 1933 he wrote of Key West, "We have a fine house here, and kids are all well"—Mellow believes he "was plainly restless".[81]

In 1933, Hemingway and Pauline went on safari to Kenya. The 10-week trip provided material for Green Hills of Africa, as well as for the short stories "The Snows of Kilimanjaro" and "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber".[82] The couple visited Mombasa, Nairobi, and Machakos in Kenya; then moved on to Tanganyika Territory, where they hunted in the Serengeti, around Lake Manyara, and west and southeast of present-day Tarangire National Park. Their guide was the noted "white hunter" Philip Percival who had guided Theodore Roosevelt on his 1909 safari. During these travels, Hemingway contracted amoebic dysentery that caused a prolapsed intestine, and he was evacuated by plane to Nairobi, an experience reflected in "The Snows of Kilimanjaro". On Hemingway's return to Key West in early 1934, he began work on Green Hills of Africa, which he published in 1935 to mixed reviews.[83]

He purchased a boat in 1934, naming it the Pilar, and began to sail the Caribbean.[84] He arrived at Bimini in 1935, where he spent a considerable amount of time.[82] During this period he worked on To Have and Have Not, published in 1937 while he was in Spain, which became the only novel he wrote during the 1930s.[85]

Spanish Civil War

Hemingway had been following developments in Spain since early in his career[86] and from 1931 it became clear that there would be another European war. Hemingway predicted war would happen in the late 1930s. Baker writes that Hemingway did not expect Spain to "become a sort of international testing-ground for Germany, Italy, and Russia before the Spanish Civil War was over".[87] Despite Pauline's reluctance, he signed with North American Newspaper Alliance to cover the Spanish Civil War,[88] and sailed from New York on February 27, 1937.[89] Journalist and writer Martha Gellhorn accompanied Hemingway. He had met her in Key West a year earlier. Like Hadley, Martha was a St. Louis native and, like Pauline, had worked for Vogue in Paris. According to Kert, Martha "never catered to him the way other women did".[90]

He arrived in Spain in March with Dutch filmmaker Joris Ivens.[91] Ivens, who was filming The Spanish Earth, intended to replace John Dos Passos with Hemingway as screenwriter. Dos Passos had left the project when his friend and Spanish translator José Robles was arrested and later executed.[92] The incident changed Dos Passos's opinion of the leftist republicans, and caused a rift with Hemingway.[93] Back in the U.S. that summer, Hemingway prepared the soundtrack for the film. It was screened at the White House in July.[94]

In late August he returned to France and flew from Paris to Barcelona and then to Valencia.[95] In September he visited the front in Belchite and then on to Teruel.[96] On his return to Madrid Hemingway wrote his only play, The Fifth Column, as the city was being bombarded by the Francoist army.[97] He went back to Key West for a few months in January 1938. It was a frustrating time: he found it hard to write, fretted over poor reviews for To Have and Have Not, bickered with Pauline, followed the news from Spain avidly and planned the next trip.[98] He took two trips to Spain in 1938. In November he visited the location of the Battle of the Ebro, the last republican stand, along with other British and American journalists.[99] They arrived to find the last bridge destroyed and had to retreat across the turbulent Ebro in a rowboat, Hemingway at the oars, "pulling for dear life".[100][101]

In early 1939, Hemingway crossed to Cuba in his boat to live in the Hotel Ambos Mundos in Havana. This was the separation phase of a slow and painful split from Pauline, which began when Hemingway met Martha Gellhorn.[102] Martha soon joined him in Cuba, and they rented Finca Vigía ("Lookout Farm"), a 15-acre (61,000 m2) property 15 miles (24 km) from Havana. That summer while visiting with Pauline and the children in Wyoming, she took the children and left him. When his divorce from Pauline was finalized, he and Martha were married on November 20, 1940, in Cheyenne, Wyoming.[103]

Hemingway followed the pattern established after his divorce from Hadley and moved again. He split his time between Cuba and the newly established resort Sun Valley.[104] He was at work on For Whom the Bell Tolls, which he began in March 1939 and finished in July 1940.[104] His pattern was to move around while working on a manuscript, and he wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls in Cuba, Wyoming, and Sun Valley.[102] Published that October,[104] it became a book-of-the-month choice, sold half a million copies within months, was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, and as Meyers describes, "triumphantly re-established Hemingway's literary reputation".[105] In January 1941, Martha was sent to China on assignment for Collier's magazine.[106] Hemingway went with her, sending in dispatches for the newspaper PM. Meyers writes that Hemingway had little enthusiasm for the trip or for China;[106] although his dispatches for PM provided incisive insights of the Sino-Japanese War according to Reynolds, with analysis of Japanese incursions into the Philippines sparking an "American war in the Pacific".[107] Hemingway returned to Finca Vigía in August and left for Sun Valley a month later.[108]

World War II

The United States entered the war after the Attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941.[109] Back in Cuba, Hemingway refitted the Pilar as a Q-boat and went on patrol for German U-boats.[note 4][19] He also created a counterintelligence unit headquartered in his guesthouse to surveil Falangists,[110] and Nazi sympathizers.[111] Martha and his friends thought his activities "little more than a diverting racket", but the FBI began watching him and compiled a 124-page file.[note 5][112] Martha wanted Hemingway in Europe as a journalist and failed to understand his reticence to take part in another European war. They fought frequently and bitterly, and he drank too much,[113] until she left for Europe to report for Collier's in September 1943.[114] On a visit to Cuba in March 1944, Hemingway was bullying and abusive with Martha. Reynolds writes that "looking backward from 1960–61 [anyone] might say that his behavior was a manifestation of the depression that eventually destroyed him".[114] A few weeks later, he contacted Collier's who made him their front-line correspondent.[115] He was in Europe from May 1944 to March 1945.[116]

When he arrived in London, he met Time magazine correspondent Mary Welsh, with whom he became infatuated. Martha had been forced to cross the Atlantic in a ship filled with explosives because Hemingway refused to help her get a press pass on a plane, and she arrived in London to find him hospitalized with a concussion from a car accident. She was unsympathetic to his plight; she accused him of being a bully and told him that she was "through, absolutely finished".[117] The last time that Hemingway saw Martha was in March 1945 as he prepared to return to Cuba;[118] their divorce was finalized later that year.[117] Meanwhile, he had asked Mary Welsh to marry him on their third meeting.[117]

Hemingway sustained a severe head-wound that required 57 stitches.[119] Still suffering symptoms of the concussion,[120] he accompanied troops to the Normandy landings wearing a large head bandage. The military treated him as "precious cargo" and he was not allowed ashore.[121] The landing craft he was on came within sight of Omaha Beach before coming under enemy fire when it turned back. Hemingway later wrote in Collier's that he could see "the first, second, third, fourth and fifth waves of [landing troops] lay where they had fallen, looking like so many heavily laden bundles on the flat pebbly stretch between the sea and first cover".[122] Mellow explains that, on that first day, none of the correspondents were allowed to land and Hemingway was returned to the Dorothea Dix.[123] Late in July, he attached himself to "the 22nd Infantry Regiment commanded by Col. Charles 'Buck' Lanham, as it drove toward Paris", and Hemingway became de facto leader to a small band of village militia in Rambouillet outside of Paris.[116] Paul Fussell remarks: "Hemingway got into considerable trouble playing infantry captain to a group of Resistance people that he gathered because a correspondent is not supposed to lead troops, even if he does it well."[19] This was, in fact, in contravention of the Geneva Convention, and Hemingway was brought up on formal charges; he said that he "beat the rap" by claiming that he only offered advice.[124]

He was present at the liberation of Paris on August 25; however contrary to legend, he was not the first into the city nor did he liberate the Ritz.[125] While there, he visited Sylvia Beach and met Picasso with Mary Welsh, and in a spirit of happiness, forgave Gertrude Stein.[126] Later that year, he observed heavy fighting at the Battle of Hürtgen Forest.[125] On December 17, 1944, he traveled to Luxembourg, in spite of illness, to report on The Battle of the Bulge. As soon as he arrived, however, Lanham referred him to the doctors, who hospitalized him with pneumonia; he recovered a week later, but most of the fighting was over.[124] He was awarded a Bronze Star for bravery in 1947, in recognition for having been "under fire in combat areas in order to obtain an accurate picture of conditions".[19]

Cuba and the Nobel Prize

Hemingway said he "was out of business as a writer" from 1942 to 1945.[127] In 1946 he married Mary, who had an ectopic pregnancy five months later. The Hemingway family suffered a series of accidents and health problems in the years following the war: in a 1945 car accident, he injured his knee and sustained another head wound. A few years later Mary broke her right and left ankles in successive skiing accidents. A 1947 car accident left Patrick with a head wound, severely ill and delirious. The doctor in Cuba diagnosed schizophrenia, and sent him for 18 sessions of electroconvulsive therapy.[128]

Hemingway sank into depression as his literary friends began to die: in 1939 William Butler Yeats and Ford Madox Ford; in 1940 F. Scott Fitzgerald; in 1941 Sherwood Anderson and James Joyce; in 1946 Gertrude Stein; and the following year in 1947, Max Perkins, Hemingway's long-time Scribner's editor, and friend.[129] During this period, he suffered from severe headaches, high blood pressure, weight problems, and eventually diabetes—much of which was the result of previous accidents and many years of heavy drinking.[130] Nonetheless, in January 1946, he began work on The Garden of Eden, finishing 800 pages by June.[note 6][131] During the post-war years, he also began work on a trilogy tentatively titled "The Land", "The Sea" and "The Air", which he wanted to combine in one novel titled The Sea Book. Both projects stalled. Mellow writes that Hemingway's inability to write was "a symptom of his troubles" during these years.[note 7][132]

In 1948, Hemingway and Mary traveled to Europe, staying in Venice for several months. While there, Hemingway fell in love with the then 19-year-old Adriana Ivancich. The platonic love affair inspired the novel Across the River and into the Trees, written in Cuba during a time of strife with Mary, and published in 1950 to negative reviews.[133] The following year, furious at the critical reception of Across the River and Into the Trees, Hemingway wrote the draft of The Old Man and the Sea in eight weeks, saying that it was "the best I can write ever for all of my life".[130] Published in September 1952,[134] The Old Man and the Sea became a book-of-the-month selection, made Hemingway an international celebrity, and won the Pulitzer Prize in May 1953. A month later he departed Cuba for his second trip to Africa.[135][136]

While in Africa, Hemingway was almost fatally injured in successive plane crashes, in January 1954. He had chartered a sightseeing flight over the Belgian Congo as a Christmas present to Mary. On their way to photograph Murchison Falls from the air, the plane struck an abandoned utility pole and was forced into a crash landing. Hemingway sustained injuries to his back and shoulder; Mary sustained broken ribs and went into shock. After a night in the brush, they chartered a boat on the river and arrived in Butiaba, where they were met by a pilot who had been searching for them. He assured them he could fly out, but the landing strip was too rough and the plane exploded in flames. Mary and the pilot escaped through a broken window. Hemingway had to smash his way out by battering the door open with his head.[137] Hemingway suffered burns and another serious head injury, that caused cerebral fluid to leak from the injury.[138] They eventually arrived in Entebbe to find reporters covering the story of Hemingway's death. He briefed the reporters and spent the next few weeks recuperating in Nairobi.[139] Despite his injuries, Hemingway accompanied Patrick and his wife on a planned fishing expedition in February, but pain caused him to be irascible and difficult to get along with.[140] When a bushfire broke out, he was again injured, sustaining second-degree burns on his legs, front torso, lips, left hand and right forearm.[141] Months later in Venice, Mary reported to friends the full extent of Hemingway's injuries: two cracked discs, a kidney and liver rupture, a dislocated shoulder and a broken skull.[140] The accidents may have precipitated the physical deterioration that was to follow. After the plane crashes, Hemingway, who had been "a thinly controlled alcoholic throughout much of his life, drank more heavily than usual to combat the pain of his injuries."[142]

In October 1954, Hemingway received the Nobel Prize in Literature. He modestly told the press that Carl Sandburg, Isak Dinesen and Bernard Berenson deserved the prize,[143] but he gladly accepted the prize money.[144] Mellow says Hemingway "had coveted the Nobel Prize", but when he won it, months after his plane accidents and their worldwide press coverage, "there must have been a lingering suspicion in Hemingway's mind that his obituary notices had played a part in the academy's decision."[145] He was still recuperating and decided against traveling to Stockholm.[146] Instead he sent a speech to be read in which he defined the writer's life:

Writing, at its best, is a lonely life. Organizations for writers palliate the writer's loneliness but I doubt if they improve his writing. He grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness and often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone and if he is a good enough writer he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day.[147][148]

Since his return from Africa, Hemingway had been slowly writing his "African Journal".[note 8][149] Late in the year and early into 1956 he was bedridden with a variety of illnesses.[149] He was ordered to stop drinking so as to mitigate liver damage, advice he initially followed but eventually disregarded.[150] In October 1956, he returned to Europe and visited ailing Basque writer Pio Baroja, who died a few weeks later. During the trip, Hemingway again became sick and was treated for a variety of ailments including liver disease and high blood pressure.[151]

In November 1956, while staying in Paris, he was reminded of trunks he had stored in the Ritz Hotel in 1928 and never retrieved. Upon re-claiming and opening the trunks, Hemingway discovered they were filled with notebooks and writing from his Paris years. Excited about the discovery, when he returned to Cuba in early 1957, he began to shape the recovered work into his memoir A Moveable Feast.[152] By 1959, he ended a period of intense activity: he finished A Moveable Feast (scheduled to be released the following year); brought True at First Light to 200,000 words; added chapters to The Garden of Eden; and worked on Islands in the Stream. The last three were stored in a safe deposit box in Havana as he focused on the finishing touches for A Moveable Feast. Reynolds claims it was during this period that Hemingway slid into depression, from which he was unable to recover.[153]

Finca Vigía became crowded with guests and tourists, as Hemingway considered a permanent move to Idaho. In 1959, he bought a home overlooking the Big Wood River, outside Ketchum and left Cuba—although he apparently remained on easy terms with the Castro government, telling The New York Times he was "delighted" with Castro's overthrow of Batista.[154][155] He was in Cuba in November 1959, between returning from Pamplona and traveling west to Idaho, and the following year for his 61st birthday; however, that year, he and Mary decided to leave after hearing the news that Castro wanted to nationalize property owned by Americans and other foreign nationals.[156] On July 25, 1960, the Hemingways left Cuba for the last time, leaving art and manuscripts in a bank vault in Havana. After the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion, Finca Vigía was expropriated by the Cuban government, complete with Hemingway's collection of about 5,000 books.[157]

Idaho and suicide

After leaving Cuba, in Sun Valley, Hemingway continued to rework the material that was published as A Moveable Feast through the 1950s.[152] In mid-1959, he visited Spain to research a series of bullfighting articles commissioned by Life magazine.[158] Life wanted only 10,000 words, but the manuscript grew out of control.[159] For the first time in his life he could not organize his writing, so he asked A. E. Hotchner to travel to Cuba to help him. Hotchner helped trim the Life piece down to 40,000 words, and Scribner's agreed to a full-length book version (The Dangerous Summer) of almost 130,000 words.[160] Hotchner found Hemingway to be "unusually hesitant, disorganized, and confused",[161] and suffering badly from failing eyesight.[162] He left Cuba for the last time on July 25, 1960. Mary went with him to New York where he set up a small office and attempted unsuccessfully to work. Soon after, he left New York, traveling without Mary to Spain to be photographed for the front cover of Life magazine. A few days later the news reported that he was seriously ill and on the verge of dying, which panicked Mary until she received a cable from him telling her, "Reports false. Enroute Madrid. Love Papa."[163] He was, in fact, seriously ill, and believed himself to be on the verge of a breakdown.[160] Feeling lonely, he took to his bed for days, retreating into silence, despite having the first installments of The Dangerous Summer published in Life that September to good reviews.[164] In October, he went back to New York, where he refused to leave Mary's apartment, presuming that he was being watched. She quickly took him to Idaho, where they were met at the train station in Ketchum by local physician George Saviers.[160]

He was concerned about finances, missed Cuba, his books, and his life there, and fretted that he would never return to retrieve the manuscripts that he had left in a bank vault.[165] He believed the manuscripts that would be published as Islands in the Stream and True at First Light were lost.[166] He became paranoid, believing that the FBI was actively monitoring his movements in Ketchum.[note 9][162] Mary was unable to care for her husband and it was anathema for a man of Hemingway's generation to accept he suffered from mental illness. At the end of November, Saviers flew him to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota on the pretext that he was to be treated for hypertension.[165] He was checked in under Saviers's name to maintain anonymity.[164]

Meyers writes that "an aura of secrecy surrounds Hemingway's treatment at the Mayo" but confirms that he was treated with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) as many as 15 times in December 1960.[167] Reynolds gained access to Hemingway's records at the Mayo, which document 10 ECT sessions. The doctors in Rochester told Hemingway the depressive state for which he was being treated may have been caused by his long-term use of Reserpine and Ritalin.[168] Of the ECT therapy, Hemingway told Hotchner, "What is the sense of ruining my head and erasing my memory, which is my capital, and putting me out of business? It was a brilliant cure, but we lost the patient."[169] In late January 1961 he was sent home, as Meyers writes, "in ruins". Asked to provide a tribute to President John F. Kennedy in February he could only produce a few sentences after a week's effort.

A few months later, on April 21, Mary found Hemingway with a shotgun in the kitchen. She called Saviers, who admitted Hemingway to the Sun Valley Hospital under sedation. Once the weather cleared, Saviers flew again to Rochester with his patient.[170] Hemingway underwent three electroshock treatments during that visit.[171] He was released at the end of June and was home in Ketchum on June 30.

Two days later Hemingway "quite deliberately" shot himself with his favorite shotgun in the early morning hours of July 2, 1961.[172] Meyers writes that he unlocked the basement storeroom where his guns were kept, went upstairs to the front entrance foyer, "pushed two shells into the twelve-gauge Boss shotgun ... put the end of the barrel into his mouth, pulled the trigger and blew out his brains."[173] In 2010, however, it was argued that Hemingway never owned a Boss and that the suicide gun was actually made by W. & C. Scott & Son, his favorite one that was used at shooting competitions in Cuba, duck hunts in Italy or at a safari in East Africa.[174]

When the authorities arrived, Mary was sedated and taken to the hospital. Returning to the house the next day, she cleaned the house and saw to the funeral and travel arrangements. Bernice Kert writes that it "did not seem to her a conscious lie" when she told the press that his death had been accidental.[175] In a press interview five years later, Mary confirmed that he had shot himself.[176] Family and friends flew to Ketchum for the funeral, officiated by the local Catholic priest, who believed that the death had been accidental.[175] An altar boy fainted at the head of the casket during the funeral, and Hemingway's brother Leicester wrote: "It seemed to me Ernest would have approved of it all."[177]

Hemingway's behavior during his final years had been similar to that of his father before he killed himself;[178] his father may have had hereditary hemochromatosis, whereby the excessive accumulation of iron in tissues culminates in mental and physical deterioration.[179] Medical records made available in 1991 confirmed that Hemingway had been diagnosed with hemochromatosis in early 1961.[180] His sister Ursula and his brother Leicester also killed themselves.[181]

Hemingway's health was further complicated by heavy drinking throughout most of his life, which exacerbated his erratic behavior, and his head injuries increased the effects of the alcohol.[130][182] The neuropsychiatrist Andrew Farah's 2017 book Hemingway's Brain, offers a forensic examination of Hemingway's mental illness. In her review of Farah's book, Beegel writes that Farah postulates Hemingway suffered from the combination of depression, the side-effects of nine serious concussions, then, she writes, "Add alcohol and stir".[183] Farah writes that Hemingway's concussions resulted in chronic traumatic encephalopathy, which eventually led to a form of dementia,[184] most likely dementia with Lewy bodies. He bases his hypothesis on Hemingway's symptoms consistent with DLB, such as the various comorbidities, and most particularly the delusions, which surfaced as early as the late 1940s and were almost overwhelming during the final Ketchum years.[185] Beegel writes that Farah's study is convincing and "should put an end to future speculation".[183]

Writing style

Following the tradition established by Mark Twain, Stephen Crane, Theodore Dreiser, and Sinclair Lewis, Hemingway was a journalist before becoming a novelist.[9] The New York Times wrote in 1926 of Hemingway's first novel, "No amount of analysis can convey the quality of The Sun Also Rises. It is a truly gripping story, told in a lean, hard, athletic narrative prose that puts more literary English to shame."[186] The Sun Also Rises is written in the spare, tight prose that made Hemingway famous, and, according to James Nagel, "changed the nature of American writing".[187] In 1954, when Hemingway was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, it was for "his mastery of the art of narrative, most recently demonstrated in The Old Man and the Sea, and for the influence that he has exerted on contemporary style."[188] Henry Louis Gates believes Hemingway's style was fundamentally shaped "in reaction to [his] experience of world war". After World War I, he and other modernists "lost faith in the central institutions of Western civilization" by reacting against the elaborate style of 19th-century writers and by creating a style "in which meaning is established through dialogue, through action, and silences—a fiction in which nothing crucial—or at least very little—is stated explicitly."[19]

Hemingway's fiction often used grammatical and stylistic structures from languages other than English.[189] Critics Allen Josephs, Mimi Gladstein, and Jeffrey Herlihy-Mera have studied how Spanish influenced Hemingway's prose,[190][189] which sometimes appears directly in the other language (in italics, as occurs in The Old Man and the Sea) or in English as literal translations. He also often used bilingual puns and crosslingual wordplay as stylistic devices.[191][192][193]

If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water. A writer who omits things because he does not know them only makes hollow places in his writing.

Because he began as a writer of short stories, Baker believes Hemingway learned to "get the most from the least, how to prune language, how to multiply intensities and how to tell nothing but the truth in a way that allowed for telling more than the truth."[195] Hemingway called his style the iceberg theory: the facts float above water; the supporting structure and symbolism operate out of sight.[195] The concept of the iceberg theory is sometimes referred to as the "theory of omission". Hemingway believed the writer could describe one thing (such as Nick Adams fishing in "Big Two-Hearted River") though an entirely different thing occurs below the surface (Nick Adams concentrating on fishing to the extent that he does not have to think about anything else).[196] Paul Smith writes that Hemingway's first stories, collected as In Our Time, showed he was still experimenting with his writing style,[197] and when he wrote about Spain or other countries he incorporated foreign words into the text, which sometimes appears directly in the other language (in italics, as occurs in The Old Man and the Sea) or in English as literal translations.[198] In general, he avoided complicated syntax. About 70 percent of the sentences are simple sentences without subordination—a simple childlike grammar structure.[199]

Jackson Benson believes Hemingway used autobiographical details as framing devices about life in general—not only about his life. For example, Benson postulates that Hemingway used his experiences and drew them out with "what if" scenarios: "what if I were wounded in such a way that I could not sleep at night? What if I were wounded and made crazy, what would happen if I were sent back to the front?"[200] Writing in "The Art of the Short Story", Hemingway explains: "A few things I have found to be true. If you leave out important things or events that you know about, the story is strengthened. If you leave or skip something because you do not know it, the story will be worthless. The test of any story is how very good the stuff that you, not your editors, omit."[201]

In the late summer that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the trees.

The simplicity of the prose is deceptive. Zoe Trodd believes Hemingway crafted skeletal sentences in response to Henry James's observation that World War I had "used up words". Hemingway offers a "multi-focal" photographic reality. His iceberg theory of omission is the foundation on which he builds. The syntax, which lacks subordinating conjunctions, creates static sentences. The photographic "snapshot" style creates a collage of images. Many types of internal punctuation (colons, semicolons, dashes, parentheses) are omitted in favor of short declarative sentences. The sentences build on each other, as events build to create a sense of the whole. Multiple strands exist in one story; an "embedded text" bridges to a different angle. He also uses other cinematic techniques of "cutting" quickly from one scene to the next; or of "splicing" a scene into another. Intentional omissions allow the reader to fill the gap, as though responding to instructions from the author, and create three-dimensional prose.[203] Conjunctions such as "and" are habitually used in place of commas; a use polysyndeton that conveys immediacy. Hemingway's polysyndetonic sentence—or in later works his use of subordinate clauses—uses conjunctions to juxtapose startling visions and images. Benson compares them to haikus.[204][205]

Many of Hemingway's followers misinterpreted his style and frowned upon expression of emotion; Saul Bellow satirized this style as "Do you have emotions? Strangle them."[206] Hemingway's intent was not to eliminate emotion, but to portray it realistically. As he explains in Death in the Afternoon: "In writing for a newspaper you told what happened ... but the real thing, the sequence of motion and fact which made the emotion and which would be as valid in a year or in ten years or, with luck and if you stated it purely enough, always, was beyond me". He tried to achieve conveying emotion with collages of images.[207] This use of an image as an objective correlative is characteristic of Ezra Pound, T. S. Eliot, James Joyce, and Marcel Proust.[208] Hemingway's letters refer to Proust's Remembrance of Things Past several times over the years, and indicate he read the book at least twice.[209]

Themes

Hemingway's writing includes themes of love, war, travel, expatriation, wilderness, and loss.[210] Critic Leslie Fiedler sees the theme he defines as "The Sacred Land"—the American West—extended in Hemingway's work to include mountains in Spain, Switzerland and Africa, and to the streams of Michigan. The American West is given a symbolic nod with the naming of the "Hotel Montana" in The Sun Also Rises and For Whom the Bell Tolls.[211] In Hemingway's Expatriate Nationalism, Jeffrey Herlihy describes "Hemingway's Transnational Archetype" as one that involves characters who are "multilingual and bicultural, and have integrated new cultural norms from the host community into their daily lives by the time plots begin."[212] In this way, "foreign scenarios, far from being mere exotic backdrops or cosmopolitan milieus, are motivating factors in-character action".[213]

In Hemingway's fiction, nature is a place for rebirth and rest; it is where the hunter or fisherman might experience a moment of transcendence at the moment they kill their prey.[214] Nature is where men exist without women: men fish; men hunt; men find redemption in nature.[211] Although Hemingway does write about sports, such as fishing, Carlos Baker notes the emphasis is more on the athlete than the sport.[215] At its core, much of Hemingway's work can be viewed in the light of American naturalism, evident in detailed descriptions such as those in "Big Two-Hearted River".[8]

Fiedler believes Hemingway inverts the American literary theme of the evil "Dark Woman" versus the good "Light Woman". The dark woman—Brett Ashley of The Sun Also Rises—is a goddess; the light woman—Margot Macomber of "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber"—is a murderess.[211] Robert Scholes says early Hemingway stories, such as "A Very Short Story", present "a male character favorably and a female unfavorably".[216] According to Rena Sanderson, early Hemingway critics lauded his male-centric world of masculine pursuits, and the fiction divided women into "castrators or love-slaves". Feminist critics attacked Hemingway as "public enemy number one", although more recent re-evaluations of his work "have given new visibility to Hemingway's female characters (and their strengths) and have revealed his own sensitivity to gender issues, thus casting doubts on the old assumption that his writings were one-sidedly masculine."[217] Nina Baym believes that Brett Ashley and Margot Macomber "are the two outstanding examples of Hemingway's 'bitch women.'"[218]

The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong in the broken places. But those that will not break it kills. It kills the very good and the very gentle and the very brave impartially. If you are none of these you can be sure it will kill you too but there will be no special hurry.

Death permeates much of Hemingway's work. Young believes the emphasis on death in "Indian Camp" was not so much on the father who kills himself, but on Nick Adams, who witnesses these events and becomes a "badly scarred and nervous young man". Young believes the archetype in "Indian Camp" holds the "master key" to "what its author was up to for some thirty-five years of his writing career".[220] Stoltzfus considers Hemingway's work to be more complex with a representation of the truth inherent in existentialism: if "nothingness" is embraced, then redemption is achieved at the moment of death. Those who face death with dignity and courage live an authentic life. Francis Macomber dies happy because the last hours of his life are authentic; the bullfighter in the corrida represents the pinnacle of a life lived with authenticity.[214] In his paper The Uses of Authenticity: Hemingway and the Literary Field, Timo Müller writes that Hemingway's fiction is successful because the characters live an "authentic life", and the "soldiers, fishers, boxers and backwoodsmen are among the archetypes of authenticity in modern literature".[221]

Emasculation is prevalent in Hemingway's work, notably in God Rest You Merry, Gentlemen and The Sun Also Rises. Emasculation, according to Fiedler, is a result of a generation of wounded soldiers; and of a generation in which women such as Brett gained emancipation. This also applies to the minor character, Frances Clyne, Cohn's girlfriend in the beginning of The Sun Also Rises. Her character supports the theme not only because the idea was presented early on in the novel but also the impact she had on Cohn in the start of the book while only appearing a small number of times.[211] In God Rest You Merry, Gentlemen, the emasculation is literal, and related to religious guilt. Baker believes Hemingway's work emphasizes the "natural" versus the "unnatural". In "An Alpine Idyll" the "unnaturalness" of skiing in the high country late spring snow is juxtaposed against the "unnaturalness" of the peasant who allowed his wife's dead body to linger too long in the shed during the winter. The skiers and peasant retreat to the valley to the "natural" spring for redemption.[215]

In recent decades, critics have characterized Hemingway's work as misogynistic and homophobic. Susan Beegel analyzed four decades of Hemingway criticism and found that "critics interested in multiculturalism" simply ignored Hemingway. Typical is this analysis of The Sun Also Rises: "Hemingway never lets the reader forget that Cohn is a Jew, not an unattractive character who happens to be a Jew but a character who is unattractive because he is a Jew." During the same decade, according to Beegel, criticism was published that investigated the "horror of homosexuality" and racism in Hemingway's fiction.[222] In an overall assessment of Hemingway's work Beegel has written: "Throughout his remarkable body of fiction, he tells the truth about human fear, guilt, betrayal, violence, cruelty, drunkenness, hunger, greed, apathy, ecstasy, tenderness, love and lust."[223]

Influence and legacy

Hemingway's legacy to American literature is his style: writers who came after him either emulated or avoided it.[224] After his reputation was established with the publication of The Sun Also Rises, he became the spokesperson for the post–World War I generation, having established a style to follow.[187] His books were burned in Berlin in 1933, "as being a monument of modern decadence", and disavowed by his parents as "filth".[225] Reynolds asserts the legacy is that "[Hemingway] left stories and novels so starkly moving that some have become part of our cultural heritage."[226] Benson believes the details of Hemingway's life have become a "prime vehicle for exploitation", resulting in a Hemingway industry.[227] The Hemingway scholar Hallengren believes the "hard-boiled style" and the machismo must be separated from the author himself.[225] Benson agrees, describing him as introverted and private as J. D. Salinger, although Hemingway masked his nature with braggadocio.[228] During World War II, Salinger met and corresponded with Hemingway, whom he acknowledged as an influence. In a letter to Hemingway, Salinger claimed their talks "had given him his only hopeful minutes of the entire war" and jokingly "named himself national chairman of the Hemingway Fan Clubs".[229] In 2002, a fossil billfish from the Danata Formation of Turkmenistan was named Hemingwaya after Hemingway, who prominently featured a marlin in The Old Man and the Sea.[230]

Mary Hemingway established the Hemingway Foundation in 1965, and in the 1970s, she donated her husband's papers to the John F. Kennedy Library. In 1980, a group of Hemingway scholars gathered to assess the donated papers, subsequently forming the Hemingway Society, "committed to supporting and fostering Hemingway scholarship", publishing The Hemingway Review.[231] His granddaughter Margaux Hemingway was a supermodel and actress and co-starred with her younger sister Mariel in the 1976 movie Lipstick.[232][233] Her death was later ruled a death by suicide.[234]

Selected works

This is a list of work that Ernest Hemingway published during his lifetime. While much of his later writing was published posthumously, they were finished without his supervision, unlike the works listed below.

- Three Stories and Ten Poems (1923)

- in our time (1924)

- In Our Time (1925)

- The Torrents of Spring (1926)

- The Sun Also Rises (1926)

- Men Without Women (1927)

- A Farewell to Arms (1929)

- Death in the Afternoon (1932)

- Winner Take Nothing (1933)

- Green Hills of Africa (1935)

- To Have and Have Not (1937)

- The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories (1938)

- For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940)

- Across the River and into the Trees (1950)

- The Old Man and the Sea (1952)

See also

References

Notes

- ^ On awarding the medal, the Italians wrote of Hemingway: "Gravely wounded by numerou s pieces of shrapnel from an enemy shell, with an admirable spirit of brotherhood, before taking care of himself, he rendered generous assistance to the Italian soldiers more seriously wounded by the same explosion and did not allow himself to be carried elsewhere until after they had been evacuated." See Mellow (1992), p. 61

- ^ Clarence Hemingway used his father's Civil War pistol to shoot himself. See Meyers (1985), 2

- ^ She would undergo sex reassignment surgery between 1988 and 1994. See Meyers (2020), 413

- ^ Germany targeted ships leaving the Lago refinery in Aruba to transport oil products to England; in 1942, more than 250 ships were destroyed. See Reynolds (2012), 336

- ^ He would remain under surveillance until his death. See Meyers (1985), 384

- ^ The Garden of Eden was published posthumously in 1986. See Meyers (1985), 436

- ^ The manuscript for The Sea Book was published posthumously as Islands in the Stream in 1970. See Mellow (1992), 552

- ^ Published in 1999 as True at First Light. See Oliver (1999), 333

- ^ The FBI had opened a file on him during World War II, when he used the Pilar to patrol the waters off Cuba, and J. Edgar Hoover had an agent in Havana watch him during the 1950s, see Mellow (1992), 597–598; and appeared to be monitoring his movements at that time, as an agent documented in a letter written a few months later, in January 1961, about Hemingway's stay at the Mayo clinic. see Meyers (1985), 543–544

Citations

- ^ Oliver (1999), 140

- ^ a b c Reynolds (2000), 17–18

- ^ Meyers (1985), 4

- ^ Oliver (1999), 134

- ^ Meyers (1985), 9

- ^ a b c Reynolds (2000), 19

- ^ Meyers (1985), 3

- ^ a b Beegel (2000), 63–71

- ^ a b c Meyers (1985), 19–23

- ^ "Star style and rules for writing". The Kansas City Star. June 26, 1999. Archived from the original on April 8, 2014.

Below are excerpts from The Kansas City Star stylebook that Ernest Hemingway once credited with containing 'the best rules I ever learned for the business of writing.'

- ^ Meyers (1985), 26

- ^ Mellow (1992), 48–49

- ^ Meyers (1985), 27–31

- ^ Hutchisson (2016), 26

- ^ a b c Mellow (1992), 57–60

- ^ Hutchisson (2016), 28

- ^ Baker (1981), 247

- ^ Baker (1981), 17

- ^ a b c d e f Putnam, Thomas (August 15, 2016). "Hemingway on War and Its Aftermath". archives.gov. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ Desnoyers, 3

- ^ Meyers (1985), 34, 37–42

- ^ Meyers (1985), 37–42

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 45–53

- ^ Reynolds (1998), 21

- ^ Mellow (1992), 101

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 56–58

- ^ a b c Kert (1983), 83–90

- ^ Oliver (1999), 139

- ^ a b c Baker (1972), 7

- ^ Meyers (1985), 60–62

- ^ a b c Meyers (1985), 70–74

- ^ Mellow (1991), 8

- ^ Meyers (1985), 77

- ^ Mellow (1992), 308

- ^ a b Reynolds (2000), 28

- ^ Spanier, 558

- ^ Meyers (1985), 77–81

- ^ Meyers (1985), 82

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 24

- ^ Desnoyers, 5

- ^ Meyers (1985), 69–70

- ^ a b Baker (1972), 15–18

- ^ Meyers (1985), 126

- ^ Baker (1972), 34

- ^ Meyers (1985), 127

- ^ Mellow (1992), 236

- ^ Mellow (1992), 314

- ^ Meyers (1985), 159–160

- ^ Baker (1972), 30–34

- ^ Meyers (1985), 117–119

- ^ Nagel (1996), 89

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 189

- ^ Reynolds (1989), vi–vii

- ^ Mellow (1992), 328

- ^ a b Baker (1972), 44

- ^ Mellow (1992), 302

- ^ Meyers (1985), 192

- ^ Baker (1972), 82

- ^ Baker (1972), 43

- ^ Mellow (1992), 333

- ^ Mellow (1992), 338–340

- ^ Meyers (1985), 172

- ^ Meyers (1985), 173, 184

- ^ Mellow (1992), 348–353

- ^ Meyers (1985), 195

- ^ Long (1932), 2–3

- ^ Robinson (2005)

- ^ Meyers (1985), 204

- ^ "1920–1929". www.kumc.edu.

- ^ Meyers (1985), 208

- ^ Mellow (1992), 367

- ^ qtd. in Meyers (1985), 210

- ^ Meyers (1985), 215

- ^ Mellow (1992), 378

- ^ Baker (1972), 144–145

- ^ Meyers (1985), 222

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 31

- ^ Oliver (1999), 144

- ^ Meyers (1985), 222–227

- ^ Mellow (1992), 376–377

- ^ Mellow (1992), 424

- ^ a b Desnoyers, 9

- ^ Mellow (1992), 337–340

- ^ Meyers (1985), 280

- ^ Meyers (1985), 292

- ^ Baker (1972), 224

- ^ Baker (1972), 227

- ^ Mellow (1992), 488

- ^ Muller (2019), 47.

- ^ Kert (1983), 287–295

- ^ Koch (2005), 87

- ^ Meyers (1985), 311

- ^ Koch (2005), 164

- ^ Baker (1972), 233

- ^ Muller (2019), 109

- ^ Muller (2019), 135–138

- ^ Koch (2005), 134

- ^ Muller (2019), 155–161

- ^ Meyers (1985), 321

- ^ Muller (2019), 203

- ^ Thomas (2001), 833

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 326

- ^ Lynn (1987), 479

- ^ a b c Meyers (1985), 334

- ^ Meyers (1985), 334–338

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 356–361

- ^ Reynolds (2012), 320

- ^ Reynolds (2012), 324–328

- ^ Reynolds (2012), 332–333

- ^ Mellow (1992), 526–527

- ^ Meyers (1985), 337

- ^ Meyers (1985), 367

- ^ Reynolds (2012), 364–365

- ^ a b Reynolds (2012), 368

- ^ Reynolds (2012), 373–374

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 398–405

- ^ a b c Kert (1983), 393–398

- ^ Meyers (1985), 416

- ^ Farah (2017), 32

- ^ Reynolds (2012), 377

- ^ Meyers (1985), 400

- ^ Reynolds (1999), 96–98

- ^ Mellow (1992), 533

- ^ a b Lynn (1987), 518–519

- ^ a b Meyers (1985) 408–411

- ^ Mellow (1992), 535–540

- ^ qtd. in Mellow (1992), 552

- ^ Meyers (1985), 420–421

- ^ Mellow (1992) 548–550

- ^ a b c Desnoyers, 12

- ^ Meyers (1985), 436

- ^ Mellow (1992), 552

- ^ Meyers (1985), 440–452

- ^ Reynolds (2012), 656

- ^ Desnoyers, 13

- ^ Meyers (1985), 489

- ^ Reynolds (2012), 550

- ^ Mellow (1992), 586

- ^ Mellow (1992), 587

- ^ a b Mellow (1992), 588

- ^ Meyers (1985), 505–507

- ^ Beegel (1996), 273

- ^ Lynn (1987), 574

- ^ Baker (1972), 38

- ^ Mellow (1992), 588–589

- ^ Meyers (1985), 509

- ^ "Ernest Hemingway The Nobel Prize in Literature 1954 Banquet Speech". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on August 2, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2009.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1954". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 511

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 291–293

- ^ Meyers (1985), 512

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 533

- ^ Reynolds (1999), 321

- ^ Mellow (1992), 494–495

- ^ Meyers (1985), 516–519

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 332, 344

- ^ Mellow (1992), 599

- ^ Meyers (1985), 520

- ^ Baker (1969), 553

- ^ a b c Reynolds (1999), 544–547

- ^ qtd. in Mellow (1992), 598–600

- ^ a b Meyers (1985), 542–544

- ^ qtd. in Reynolds (1999), 546

- ^ a b Mellow (1992), 598–601

- ^ a b Reynolds (1999), 348

- ^ Reynolds (1999), 354

- ^ Meyers (1985), 547–550

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 350

- ^ Hotchner (1983), 280

- ^ Meyers (1985), 551

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 355

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 16

- ^ Meyers (1985), 560

- ^ "Hemingway's Suicide Gun". Garden & Gun. October 20, 2010. Retrieved July 21, 2024.

- ^ a b Kert (1983), 504

- ^ Gilroy, Harry (August 23, 1966). "Widow Believes Hemingway Committed Suicide; She Tells of His Depression and His 'Breakdown' Assails Hotchner Book". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ Hemingway (1996), 14–18

- ^ Burwell (1996), 234

- ^ Burwell (1996), 14

- ^ Burwell (1996), 189

- ^ Oliver (1999), 139–149

- ^ Farah, (2017), 43

- ^ a b Beegel, (2017), 122–124

- ^ Farah, (2017), 39–40

- ^ Farah, (2017), 56

- ^ "Marital Tragedy". The New York Times. October 31, 1926. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Nagel (1996), 87

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1954". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

- ^ a b Josephs (1996), 221–235

- ^ Herlihy-Mera, Jeffrey (2012). "Ernest Hemingway in Spain: He was a sort of Joke, in Fact". The Hemingway Review. 31: 84–100 https://www.academia.edu/1258702/Ernest_Hemingway_in_Spain_He_was_a_Sort_of_Joke_in_Fact. doi:10.1353/hem.2012.0004.

- ^ Gladstein, Mimi (2006). "Bilingual Wordplay: Variations on a Theme by Hemingway and Steinbeck". The Hemingway Review. 26: 81–95 https://muse.jhu.edu/article/205022/summary. doi:10.1353/hem.2006.0047.

- ^ Herlihy-Mera, Jeffrey (2017). "Cuba in Hemingway". The Hemingway Review. 36 (2): 8–41 https://www.academia.edu/33255402/Cuba_in_Hemingway. doi:10.1353/hem.2017.0001.

- ^ Herlihy, Jeffrey (2009). "Santiago's Expatriation from Spain". The Hemingway Review. 28: 25–44 https://www.academia.edu/1548905/Santiagos_Expatriation_from_Spain_and_Cultural_Otherness_in_Hemingways_the_Old_Man_and_the_Sea. doi:10.1353/hem.0.0030.

- ^ qtd. in Oliver (1999), 322

- ^ a b Baker (1972), 117

- ^ Oliver (1999), 321–322

- ^ Smith (1996), 45

- ^ Gladstein (2006), 82–84

- ^ Wells (1975), 130–133

- ^ Benson (1989), 351

- ^ Hemingway (1975), 3

- ^ qtd. in Mellow (1992), 379

- ^ Trodd (2007), 8

- ^ McCormick, 49

- ^ Benson (1989), 309

- ^ qtd. in Hoberek (2005), 309

- ^ Hemingway, (1932), 11–12

- ^ McCormick, 47

- ^ Burwell (1996), 187

- ^ Svoboda (2000), 155

- ^ a b c d Fiedler (1975), 345–365

- ^ Herlihy (2011), 49

- ^ Herlihy (2011), 3

- ^ a b Stoltzfus (2005), 215–218

- ^ a b Baker (1972), 120–121

- ^ Scholes (1990), 42

- ^ Sanderson (1996), 171

- ^ Baym (1990), 112

- ^ Hemingway, Ernest. (1929) A Farewell to Arms. New York: Scribner's

- ^ Young (1964), 6

- ^ Müller (2010), 31

- ^ Beegel (1996), 282

- ^ "Susan Beegel: What I like about Hemingway". kansascity.com. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ Oliver (1999), 140–141

- ^ a b Hallengren, Anders. "A Case of Identity: Ernest Hemingway". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ Reynolds (2000), 15

- ^ Benson (1989), 347

- ^ Benson (1989), 349

- ^ Baker (1969), 420

- ^ Ellis, Richard (April 15, 2013). Swordfish: A Biography of the Ocean Gladiator. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-92292-8.

- ^ "Leadership". The Hemingway Society. April 18, 2021. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

Carl Eby Professor of English Appalachian State University, President (2020–2022); Gail Sinclair Rollins College, Vice President and Society Treasurer (2020–2022); Verna Kale The Pennsylvania State University, Ernest Hemingway Foundation Treasurer (2018–2020);

- ^ Rainey, James (August 21, 1996). "Margaux Hemingway's Death Ruled a Suicide". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 16, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- ^ Holloway, Lynette (July 3, 1996). "Margaux Hemingway Is Dead; Model and Actress Was 41". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

- ^ "Coroner Says Death of Actress Was Suicide". The New York Times. Associated Press. August 21, 1996. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 4, 2023.

Sources

- Baker, Carlos. (1969). Ernest Hemingway: A Life Story. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 978-0-02-001690-8

- Baker, Carlos. (1972). Hemingway: The Writer as Artist. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01305-3

- Baker, Carlos. (1981). "Introduction" in Ernest Hemingway Selected Letters 1917–1961. New York: Scribner's. ISBN 978-0-684-16765-7

- Banks, Russell. (2004). "PEN/Hemingway Prize Speech". The Hemingway Review. Volume 24, issue 1. 53–60

- Baym, Nina. (1990). "Actually I Felt Sorry for the Lion", in Benson, Jackson J. (ed.), New Critical Approaches to the Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-1067-9

- Beegel, Susan. (1996). "Conclusion: The Critical Reputation", in Donaldson, Scott (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Ernest Hemingway. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45574-9

- Beegel, Susan (2000). "Eye and Heart: Hemingway's Education as a Naturalist", in Wagner-Martin, Linda (ed.), A Historical Guide to Ernest Hemingway. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512152-0

- Beegel, Susan. (2017) "Review of Hemingway's Brain, by Andrew Farah". The Hemingway Review. Volume 37, no. 1. 122–127.

- Benson, Jackson. (1989). "Ernest Hemingway: The Life as Fiction and the Fiction as Life". American Literature. Volume 61, issue 3. 354–358

- Benson, Jackson. (1975). The Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway: Critical Essays. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-0320-6

- Burwell, Rose Marie. (1996). Hemingway: the Postwar Years and the Posthumous Novels. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-48199-1

- Desnoyers, Megan Floyd. "Ernest Hemingway: A Storyteller's Legacy" Archived August 23, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library Online Resources. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Retrieved November 30, 2011.

- Farah, Andrew. (2017). Hemingway's Brain. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-61117-743-5

- Fiedler, Leslie. (1975). Love and Death in the American Novel. New York: Stein and Day. ISBN 978-0-8128-1799-7

- Gladstein, Mimi. (2006). "Bilingual Wordplay: Variations on a Theme by Hemingway and Steinbeck" The Hemingway Review Volume 26, issue 1. 81–95.

- Griffin, Peter. (1985). Along with Youth: Hemingway, the Early Years. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-503680-0

- Hemingway, Ernest. (1929). A Farewell to Arms. New York: Scribner. ISBN 978-1-4767-6452-8

- Hemingway, Ernest. (1932). Death in the Afternoon. New York. Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-85922-4

- Hemingway, Ernest. (1975). "The Art of the Short Story", in Benson, Jackson (ed.), New Critical Approaches to the Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-1067-9

- Hemingway, Leicester. (1996). My Brother, Ernest Hemingway. New York: World Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-56164-098-0

- Herlihy, Jeffrey. (2011). Hemingway's Expatriate Nationalism. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-3409-9

- Hoberek, Andrew. (2005). Twilight of the Middle Class: Post World War II fiction and White Collar Work. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12145-1

- Hotchner, A. E. (1983). Papa Hemingway: A personal Memoir. New York: Morrow. ISBN 9781504051156

- Hutchisson, James M. (2016). Ernest Hemingway: A New Life. Penn State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-07534-1

- Josephs, Allen. (1996). "Hemingway's Spanish Sensibility", in Donaldson, Scott (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Ernest Hemingway. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45574-9

- Kert, Bernice. (1983). The Hemingway Women. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31835-7

- Koch, Stephen. (2005). The Breaking Point: Hemingway, Dos Passos, and the Murder of Jose Robles. New York: Counterpoint. ISBN 978-1-58243-280-9

- Long, Ray – editor. (1932). "Why Editors Go Wrong: 'Fifty Grand' by Ernest Hemingway", 20 Best Stories in Ray Long's 20 Years as an Editor. New York: Crown Publishers. 1–3

- Lynn, Kenneth. (1987). Hemingway. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-38732-4

- McCormick, John (1971). American Literature 1919–1932. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7100-7052-4

- Mellow, James. (1992). Hemingway: A Life Without Consequences. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-37777-2

- Mellow, James. (1991). Charmed Circle: Gertrude Stein and Company. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-47982-7

- Meyers, Jeffrey. (1985). Hemingway: A Biography. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-42126-0

- Meyers, Jeffrey. (2020). "Gregory Hemingway: Transgender Tragedy". American Imago, Volume 77, issue 2. 395–417

- Miller, Linda Patterson. (2006). "From the African Book to Under Kilimanjaro". The Hemingway Review, Volume 25, issue 2. 78–81

- Muller, Gilbert. (2019). Hemingway and the Spanish Civil War. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-030-28124-3

- Müller, Timo. (2010). "The Uses of Authenticity: Hemingway and the Literary Field, 1926–1936". Journal of Modern Literature. Volume 33, issue 1. 28–42

- Nagel, James. (1996). "Brett and the Other Women in The Sun Also Rises", in Donaldson, Scott (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Ernest Hemingway. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45574-9

- Oliver, Charles. (1999). Ernest Hemingway A to Z: The Essential Reference to the Life and Work. New York: Checkmark Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-3467-3

- Pizer, Donald. (1986). "The Hemingway: Dos Passos Relationship". Journal of Modern Literature. Volume 13, issue 1. 111–128

- Reynolds, Michael (2000). "Ernest Hemingway, 1899–1961: A Brief Biography", in Wagner-Martin, Linda (ed.), A Historical Guide to Ernest Hemingway. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512152-0

- Reynolds, Michael. (1999). Hemingway: The Final Years. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-32047-3

- Reynolds, Michael. (1989). Hemingway: The Paris Years. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31879-1

- Reynolds, Michael. (1998). The Young Hemingway. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-31776-3

- Reynolds, Michael. (2012). Hemingway: The 1930s through the final years. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-34320-5

- Robinson, Daniel. (2005). "My True Occupation is That of a Writer: Hemingway's Passport Correspondence". The Hemingway Review. Volume 24, issue 2. 87–93

- Sanderson, Rena. (1996). "Hemingway and Gender History", in Donaldson, Scott (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Ernest Hemingway. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45574-9

- Scholes, Robert. (1990). "New Critical Approaches to the Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway", in Benson, Jackson J., Decoding Papa: 'A Very Short Story' as Work and Text. 33–47. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-1067-9

- Smith, Paul (1996). "1924: Hemingway's Luggage and the Miraculous Year", in Donaldson, Scott (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Ernest Hemingway. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45574-9

- Spanier, Sandra (ed.) et al. (2024), "The Letters of Ernest Hemingway Vol. 6 1934-1936." Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89738-9

- Stoltzfus, Ben. (2005). "Sartre, 'Nada,' and Hemingway's African Stories". Comparative Literature Studies. Volume 42, issue 3. 205–228

- Svoboda, Frederic. (2000). "The Great Themes in Hemingway", in Wagner-Martin, Linda (ed.), A Historical Guide to Ernest Hemingway. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512152-0

- Thomas, Hugh. (2001). The Spanish Civil War. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 978-0-375-75515-6

- Trodd, Zoe. (2007). "Hemingway's Camera Eye: The Problems of Language and an Interwar Politics of Form". The Hemingway Review. Volume 26, issue 2. 7–21