Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine الجبهة الشعبية لتحرير فلسطين | |

|---|---|

| |

| General Secretary | Ahmad Sa'adat (imprisoned) |

| Deputy General Secretary | Jamil Mezher |

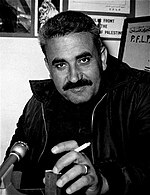

| Founder | George Habash |

| Founded | 1967 |

| Headquarters | Damascus, Syria |

| Paramilitary wing | Abu Ali Mustafa Brigades |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Far-left |

| National affiliation | Palestine Liberation Organization Democratic Alliance List |

| International affiliation | International Communist Seminar (defunct) Axis of Resistance |

| Legislative Council (2006, defunct) | 3 / 132 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| www | |

The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP; Arabic: الجبهة الشعبية لتحرير فلسطين, romanized: al-Jabha ash-Shaʿbīyya li-Taḥrīr Filasṭīn)[3] is a secular Palestinian Marxist–Leninist and revolutionary socialist organization founded in 1967 by George Habash. It has consistently been the second-largest of the groups forming the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the largest being Fatah.

The PFLP has generally taken a hard line on Palestinian national aspirations, opposing the more moderate stance of Fatah. It does not recognize Israel and promotes a one-state solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. The military wing of the PFLP is called the Abu Ali Mustafa Brigades.

The PFLP pioneered armed aircraft-hijackings in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[4] More recently, the group has participated in the Israel–Hamas war (2023–present) alongside Hamas and other allied Palestinian factions.[5][6][7][8] It has been designated a terrorist organization by the United States,[9] Japan,[10] Canada,[11] and the European Union.[12]

Ahmad Sa'adat, who was sentenced in 2006 to 30 years in an Israeli prison, has served as General Secretary of the PFLP since 2001. As of 2015[update], the PFLP boycotts participation in the PLO Executive Committee[13][14][15] and the Palestinian National Council.[16]

History

Arab Nationalist Movement

The PFLP grew out of the Harakat al-Qawmiyyin al-Arab, or Arab Nationalist Movement (ANM), founded in 1953 by George Habash, a Palestinian Christian from Lydda. In 1948, 19-year-old Habash, a medical student, went to his home town of Lydda during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War to help his family. While he was there, the Israel Defense Forces attacked the city and forced most of its civilian population to leave in what became known as the Lydda Death March. They marched for three days without food or water until they reached the Arab armies' front lines, leading to the death of his sister. Habash finished his medical education in Lebanon at the American University in Beirut, graduating in 1951.[17]

In an interview with US journalist John K. Cooley, Habash argued for viewing "the liberation of Palestine as something not to be isolated from events in the rest of the Arab world" and identified "the main reason for [Palestinians'] defeat" as triumph of "the scientific society of Israel" over "our own backwardness in the Arab world"; because of this, he "called for the total rebuilding of Arab society into a twentieth-century society" and a "scientific and technical renaissance in the Arab world".[18] The ANM was founded in this nationalist spirit. "[We] held the 'Guevara view' of the 'revolutionary human being'", Habash told Cooley. "A new breed of man had to emerge, among the Arabs as everywhere else. This meant applying everything in human power to the realization of a cause."[18]

The ANM formed underground branches in several Arab countries, including Libya, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, then still under British rule. It adopted secularism and socialist economic ideas, and pushed for armed struggle. In collaboration with the Palestinian Liberation Army, the ANM established Abtal al-Audah (Heroes of the Return) as a commando group in 1966.

Formation of the PFLP

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

After the Six-Day War of June 1967, ANM merged in August with two other groups, Youth for Revenge and Ahmed Jibril's Syrian-backed Palestine Liberation Front, to form the PFLP, with Habash as leader.[citation needed] Three other independent groups, namely Heroes of the Return, the National Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and the Independent Palestine Liberation Front, also met with Habash to form the PFLP.[19]

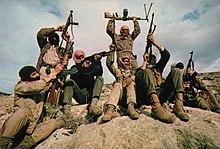

By early 1968, the PFLP had trained between one and three thousand guerrillas. It had the financial backing of Syria, and was headquartered there, and one of its training camps was based in as-Salt, Jordan. In 1969, the PFLP declared itself a Marxist–Leninist organization, but it has remained faithful to Pan-Arabism, seeing the Palestinian struggle as part of a wider uprising against Western imperialism, which also aims to unite the Arab world by overthrowing "reactionary" regimes. It published a magazine, al-Hadaf (The Target, or Goal), which was edited by Ghassan Kanafani.

Operations

The PFLP gained notoriety in the late 1960s and early 1970s for a series of armed attacks and aircraft hijackings, including on non-Israeli targets. Abu Ali Mustafa Brigades also claimed responsibility for several suicide attacks during the Al-Aqsa Intifada. See #Armed attacks of the PFLP below.

Breakaway organizations

In 1967, Palestinian Popular Struggle Front (PPSF) broke away from the PFLP.

In 1968, Ahmed Jibril broke away from the PFLP to form the Syrian-backed Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command (PFLP-GC).

In 1969, the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP) formed as a separate, ostensibly Maoist, organization under Nayef Hawatmeh and Yasser Abd Rabbo, initially as the PDFLP.

In 1972, the Popular Revolutionary Front for the Liberation of Palestine was formed following a split in PFLP.

The PFLP had a troubled relationship with George Habash's one-time deputy, Wadie Haddad, who was eventually expelled because he refused orders to stop attacks and kidnapping operations abroad. Haddad has been identified in released Soviet archival documents as having been a KGB intelligence agent in place, who in 1975 received arms for the movement directly from Soviet sources in a nighttime transfer in the Sea of Aden.[20]

PLO membership

The PFLP joined the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the umbrella organization of the Palestinian national movement, in 1968, becoming the second-largest faction after Yassir Arafat's Fatah.[19] In 1974, it withdrew from the PLO Executive Committee (but not from the PLO) to join the Rejectionist Front following the creation of the PLO's Ten Point Program, accusing the PLO of abandoning the goal of destroying Israel outright in favor of a binational solution, which was opposed by the PFLP leadership.[21] It rejoined the executive committee in 1981.[22]

In December 1993 PFLP withdrew from the PLO and became one of the ten founding members of the Damascus-based Alliance of Palestinian Forces, eight of which had been members of the PLO, which was opposed to the Oslo Accords process. PFLP withdrew from APF in 1998. Currently, the PFLP is boycotting participation in the PLO Executive Committee[13] and the Palestinian National Council.[16]

In December 2009, around 70,000 supporters demonstrated in Gaza to celebrate the PFLP's 42nd anniversary.[23]

After the Oslo Accords

After the occurrence of the First Intifada and the subsequent Oslo Accords the PFLP had difficulty establishing itself in the West Bank and Gaza Strip. At that time (1993–96) the popularity of Hamas was rapidly increasing in the wake of[colloquialism] their successful strategy of suicide bombings devised by Yahya Ayyash ("the Engineer"). The dissolution of the Soviet Union together with the rise of Islamism—and particularly the increased popularity of the Islamist groups Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad—disoriented many left activists who had looked towards the Soviet Union, and has marginalized the PFLP's role in Palestinian politics and armed resistance. However, the organization retains considerable political influence within the PLO, since no new elections have been held for the organization's legislative body, the PNC.

The PFLP developed contacts at this time with Islamic fundamentalist groups linked to Iran – both Palestinian Hamas, and the Lebanon-based Hezbollah. The PLO's agreement with Israel in September 1993, and negotiations which followed, further isolated it from the umbrella organization and led it to conclude a formal alliance with the Iranian backed groups.[24]

As a result of its post-Oslo weakness, the PFLP has been forced to adapt slowly and find partners among politically active, preferably young, Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, in order to compensate for their dependence on their aging commanders returning from or remaining in exile.[citation needed] The PFLP has therefore formed alliances with other leftist groups formed within the Palestinian Authority, including the Palestinian People's Party and the Popular Resistance Committees of Gaza.[citation needed]

In 1990, the PFLP transformed its Jordan branch into a separate political party, the Jordanian Popular Democratic Unity Party. From its foundation, the PFLP sought superpower patrons, early on developing ties with the Soviet Union, the People's Republic of China, and, at various times, with regional powers such as Syria, South Yemen, Libya, North Korea, and Iraq, as well as with left-wing groups around the world, including the FARC and the Japanese Red Army.[25][26] When that support diminished or stopped, in the late 1980s and 1990s, the PFLP sought new allies and developed contacts with Islamist groups linked to Iran, despite the PFLP's strong adherence to secularism and anti-clericalism. The relationship between the PFLP and the Islamic Republic of Iran has fluctuated – it strengthened as a result of Hamas moving away from Iran due to differing positions on the Syrian Civil War. Iran rewarded the PFLP for its pro-Assad stance with an increase in financial and military assistance.[27] The PFLP has been accused by Israel of diverting European humanitarian aid from Palestinian NGOs to itself.[28]

Elections in the Palestinian Authority

Following the death of Yasser Arafat in November 2004, the PFLP entered discussions with the DFLP and the Palestinian People's Party aimed at nominating a joint left-wing candidate for the Palestinian presidential election to be held on 9 January 2005. These discussions were unsuccessful, so the PFLP decided to support the independent Palestinian National Initiative's candidate Mustafa Barghouti, who gained 19.48% of the vote.

In the municipal elections of December 2005 it had more success, e.g. in al-Bireh and Ramallah, and winning the mayorship of Bir Zeit.[29] There are conflicting reports about the political allegiance of Janet Mikhail and Victor Batarseh, the mayors of Ramallah and Bethlehem; they may be close to the PFLP without being members.[according to whom?]

The PFLP participated in the Palestinian legislative elections of 2006 as the "Martyr Abu Ali Mustafa List". It won 4.2% of the popular vote, winning three of the 132 seats in the Palestinian Legislative Council. Its deputies are Ahmad Sa'adat, Jamil Majdalawi, and Khalida Jarrar. In the lists, its best vote was 9.4% in Bethlehem, followed by 6.6% in Ramallah and al-Bireh, and 6.5% in North Gaza. Sa'adat was sentenced in December 2006 to 30 years in an Israeli prison.

Successors to George Habash

At the PFLP's Sixth National Conference in 2000, Habash stepped down as General Secretary. Abu Ali Mustafa was elected to replace him, but was assassinated on 27 August 2001 when an Israeli helicopter fired rockets at his office in the West Bank town of Ramallah.

After Mustafa's death, the Central Committee of the PFLP on 3 October 2001 elected Ahmad Sa'adat as General Secretary. He has held that position, though since 2002 he has been incarcerated in Palestinian and Israeli prisons.

Attitude to the peace process

When it was formed in the late 1960s the PFLP supported the established line of most Palestinian guerrilla fronts and ruled out any negotiated settlement with Israel that would result in two states between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. Instead, George Habash in particular, and various other leaders in general advocated one state with an Arab identity in which Jews were entitled to live with the same rights as any minority. The PFLP declared that its goal was to "create a people's democratic Palestine, where Arabs and Jews would live without discrimination, a state without classes and national oppression, a state which allows Arabs and Jews to develop their national culture."[citation needed]

The PFLP platform never compromised on key points such as the overthrow of conservative or monarchist Arab states like Morocco and Jordan, the Right of Return of all Palestinian refugees to their homes in pre-1948 Palestine, or the use of the liberation of Palestine as an impetus for achieving Arab unity – reflecting its beginnings in the Pan-Arab ANM. It opposed the Oslo Accords and was for a long time opposed to the idea of a two-state solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, but in 1999 came to an agreement with the PLO leadership regarding negotiations with the Israeli government. However, in May 2010, PFLP general secretary Ahmad Sa'adat called for an end to the PLO's negotiations with Israel, saying that only a one-state solution was possible.[2]

In January 2011, the PFLP declared that the Camp David Accords stood for "subservience, submission, dictatorship and silence", and called for social and political revolution in Egypt.[30]

In December 2013, the PFLP stated: "Hamas is a vital part of the Palestinian national movement, and this is the position of the PFLP."[31]

Armed attacks

Armed attacks before 2000

The PFLP gained notoriety in the late 1960s and early 1970s for a series of armed attacks and aircraft hijackings, including on non-Israeli targets:

- The hijacking of El Al Flight 426 from Rome to Lod airport in Israel on 23 July 1968.[32] The Western media reported that the flight was targeted because the PFLP believed Israeli general Yitzhak Rabin, who was Israeli ambassador to the US, was on board. Several individuals involved with the hijacking, including Leila Khaled deny this. The plane was diverted to Algiers, where 21 passengers and 11 crew members were held for 39 days, until 31 August.

- Gunmen opened fire on El Al Flight 253 in Athens about to take off for New York on 26 December 1968, killing one Israeli – this prompted a reprisal by Israel destroying airliners in Beirut.

- An attack on El Al Flight 432 passengers jet at Zürich airport on 18 February 1969, killing the co-pilot and wounding the pilot; an Israeli undercover agent thwarted the hijacking after killing the terrorist leader.

- Bombings by Rasmea Odeh and other PFLP members killed 21-year-old Leon Kanner of Netanya and 22-year-old Eddie Joffe on 21 February 1969.[33][34][35] The two were killed by a bomb placed in a crowded Jerusalem SuperSol supermarket which the two students stopped in at to buy groceries for a field trip.[36][37] The same bomb wounded 9 others.[38] A second bomb was found at the supermarket, and defused.[34] Odeh was also convicted of bombing and damaging the British Consulate four days later.[39][40][41][42] In 1980, Odeh was among 78 prisoners released by Israel in an exchange with the PFLP for one Israeli soldier captured in Lebanon.[33][36][37]

- The hijacking of TWA Flight 840 from Los Angeles to Damascus on 29 August 1969 by a PFLP cell led by Leila Khaled, who became the PFLP's most noted recruit. Two Israeli passengers were held for 44 days.

- On 6 September 1970, the PFLP, including Leila Khaled, hijacked four passenger aircraft from Pan Am, TWA and Swissair on flights to New York from Brussels, Frankfurt and Zürich, and failed in an attempt to hijack an El Al aircraft which landed safely in London after one hijacker was killed and the other overpowered; and on 9 September 1970, hijacked a BOAC flight from Bahrain to London via Beirut. The Pan Am flight was diverted to Cairo; the TWA, Swissair and BOAC flights were diverted to Dawson's Field in Zarqa, Jordan. The TWA, Swissair and BOAC aircraft were subsequently blown up by the PFLP on 12 September, in front of the world media, after all passengers had been taken off the planes. The event is significant, as it was cited as a reason for the Black September clashes between Palestinian and Jordanian forces.

- On 30 May 1972, 28 passengers were gunned down at Ben Gurion International Airport by members of the Japanese Red Army in collaboration with the PFLP's Waddie Haddad in what became known as the Lod Airport massacre. Haddad had been ordered to stop planning operations, and ordered the attack without the PFLP's knowledge.

- On 13 October 1977, the PFLP hijacked Lufthansa Flight 181, a Boeing 737 flying from Palma de Mallorca to Frankfurt. After various stopovers the pilot was killed. The remaining passengers and crew were eventually rescued by German counter-terrorism special forces.

- On 12 April 1984 a bus from Tel Aviv was hijacked. Bassam Abu Sharif in Damascus issued a statement in the name of the PFLP claiming responsibility.[43]

- On 8 June 1990 a clash occurred near Shuwayya in South Lebanon in which four members of the PFLP were killed by the South Lebanon Army (SLA).[44]

- On 27 November 1990 five elite Israeli soldiers and two PFLP fighters were killed in the South Lebanon security zone.[45]

Armed attacks after 2000

The PFLP's Abu Ali Mustafa Brigades has carried out attacks on both civilians and military targets during the Al-Aqsa Intifada. Some of these attacks are:

- The killing of Meir Lixenberg, councillor and head of security in four settlements, who was shot while travelling in his car in the West Bank on 27 August 2001. PFLP claimed that this was a retaliation for the killing of Abu Ali Mustafa.[46][47]

- 21 October 2001 assassination of Israeli Minister for Tourism Rehavam Zeevi by Hamdi Quran.

- The PFLP claimed responsibility for the November 2014 Jerusalem synagogue massacre in which four Jewish worshippers and a policeman were killed with axes, knives, and a gun, while seven were injured.[48][49][50][51]

- On 29 June 2015, the PFLP claimed responsibility for an attack in which Palestinians in a vehicle fired on a passing Israeli car. Four people were injured; one was severely injured and died the next day in hospital.[52][53]

- Israeli police suspect the PFLP to be responsible for the 2019 murder of Israeli teenager Rina Shnerb.[54][55][56]

- Israel–Hamas war (2023-present): the Abu Ali Mustafa Brigades published videos of it storming Israeli watchtowers during the 7 October Hamas-led attacks into Israel, [57] and has since fought alongside Hamas and other allied factions in multiple battles inside the Gaza Strip.[5][6][7][8]

Assassinations of leaders

2024 Israeli invasion of Lebanon

Three PFLP leaders, Imad Audi, PFLP’s military leader in Lebanon; and Mohammad Abdel Aal and Abdel Rahman Abdel Aal, members of the group’s political bureau, targeted and assassinated in Beirut’s central Kola district on 29 September 2024 Sunday night, during the September 2024 Lebanon strikes by Israel.[58][59]

See also

- Arab Socialist Action Party

- List of political parties in the State of Palestine

- Palestinian domestic weapons production

- Mohamed Boudia

- Carlos the Jackal

- Revolutionare Zellen

- Blekingegade Gang

- Islamic Jihad Movement in Palestine

References

- ^ Profile: Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine BBC News, 18 November 2014

- ^ a b "Jailed PFLP leader: Only a one-state solution is possible". Haaretz. 29 April 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ "Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine | Palestinian political organization | Resistance, Activism, Liberation | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 17 January 2024. Retrieved 22 January 2024.

- ^ "Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine". BBC News. 26 January 2008. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Not only Hamas: eight factions at war with Israel in Gaza". Newsweek. 7 November 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ a b "PFLP says it will target British forces if they are deployed in Gaza". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

The military wing of the PFLP, which was founded by leftists in 1967, has carried out sporadic attacks since 7 October in retaliation for Israel's assault on Gaza.

- ^ a b "'Operation Al-Aqsa Flood' Day 86: Israel falls in 'serious strategic trap' in Gaza as Netanyahu vows to fight 'for months'". Mondoweiss. 31 December 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ a b "The Order of Battle of Hamas' Izz al Din al Qassem Brigades, Part 1: North and Central Gaza". Institute for the Study of War. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ "Foreign Terrorist Organizations". U.S. Department of State (2009-2017.state.gov).

- ^ "MOFA: Implementation of the Measures including the Freezing of Assets against Terrorists and the Like". www.mofa.go.jp. Archived from the original on 6 April 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ^ "About the listing process". www.publicsafety.gc.ca. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ "EUR-Lex – Official Journal of the European Union". lex.europa.eu.

- ^ a b Ibrahim, Arwa (13 February 2015). "PROFILE: The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine". Middle East Eye.

- ^ "Bringing the PFLP back into PLO fold?". Ma'an News Agency. 2 October 2010.

- ^ "Profile: Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP)". BBC News. 18 November 2014.

- ^ a b Sawafta, Ali (30 April 2018). "Palestinian forum convenes after 22 years, beset by division". reuters.com.

- ^ Kazziha, Walid, Revolutionary Transformation in the Arab World: Habash and his Comrades from Nationalism to Marxism. p. 17–18

- ^ a b Cooley, John K. (1973). Green March Black September: The Story of the Palestinian Arabs. London: Frank Cass & Co,. Ltd. p. 135. ISBN 0-7146-2987-1.

- ^ a b Alexander, Yonah (1 January 2003). "Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine". Palestinian Secular Terrorism: Profiles of Fatah, Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command, and Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Ardsley, NY: Transnational Publishers. pp. 33–39. doi:10.1163/9789004479500_004. ISBN 9789004479500.

- ^ "Welcome bukovsky-archives.net - Hostmonster.com" (PDF). www.bukovsky-archives.net.

- ^ Parkinson, Sarah E. (2023). Beyond the Lines: Social Networks and Palestinian Militant Organizations in Wartime Lebanon. Cornell University Press. p. 40. hdl:20.500.12657/62032. ISBN 978-1-5017-6630-5.

- ^ Parkinson 2023, pp. 47–48.

- ^ "Revolutionary roses". Al Ahram. 17 March 2010. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ The PFLP's Changing Role in the Middle East, Harold Cubert, 1997, p.xiii

- ^ "How North Korea supports Palestine and aided Hamas | NK News". 20 May 2021. Archived from the original on 20 May 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ United States; Department of State; Office for Combatting Terrorism; United States; Department of State; Office of the Ambassador at Large for Counter-Terrorism; United States; Department of State; Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism (1983). "Patterns of global terrorism". Patterns of Global Terrorism: 20 – via WorldCat.

- ^ "Iran Increases Aid to PFLP Thanks to Syria Stance". Al-Monitor. 17 September 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ "Four Palestinians to be charged with diverting European aid to terrorism". The Jerusalem Post.

- ^ Nassar Ibrahim (22 December 2005). "Palestinian Municipal Elections: The Left is advancing, while Hamas capitalizes on the decline of Fatah". Alternatives International. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ "PFLP salutes the Egyptian people and their struggle". Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). 27 January 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ "PFLP: Hamas is part of the Palestinian national movement and we do not call upon them to abandon their ideology". Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). 30 December 2013. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ Mark Ensalaco (2008). Middle Eastern Terrorism: From Black September to September 11. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8122-4046-7. JSTOR j.ctt3fhmb0.

- ^ a b Michael Tarm (24 October 2013). "Rasmieh Yousef Odeh, Community Activist, Accused Of Hiding Terror Conviction To Gain Citizenship". The Huffington Post.

- ^ a b "Jerusalem Supersol Re-opens for Business; 2 Young Bombing Victims Are Buried". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 24 February 1969.

- ^ "Arab-American activist on trial for allegedly concealing terror role in immigration papers". The Guardian. 5 November 2014.

- ^ a b "Trial set for Jerusalem terror convict who moved to US". The Times of Israel. 3 September 2014.

- ^ a b "Palestinian convicted of two bombings back in U.S. court over immigration fraud". Haaretz. 2 September 2014.

- ^ Jillian Kay Melchior (26 February 2014). "Convicted Terrorist Worked as Obamacare Navigator in Illinois". National Review Online.

- ^ "Trial set for U.S.-Palestinian immigrant convicted in Israel deaths; Rasmieh Odeh is accused of hiding she was convicted in Israel for terror attacks from American immigration officials". Haaretz. 3 October 2014.

- ^ Lorraine Swanson (21 October 2014). "Evergreen Park Woman Accused of Hiding Terrorist Past". Evergreen Park, Illinois Patch.

- ^ "Evergreen Park woman Rasmieh Odeh charged with lying about Palestinian terrorist past". ABC13 Houston. 23 October 2013.

- ^ Jason Meisner (22 October 2013). "Feds: Woman hid terror conviction to get citizenship". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ The Times (London), 14 April 1984. Robert Fisk.

- ^ Middle East International No 377, 8 June 1990, Publishers Lord Mayhew, Dennis Walters MP; “Fourteen days in brief” p. 15

- ^ Middle East International No 389, 7 December 1990, Publishers Lord Mayhew, Dennis Walters MP; Hai’m Baram p.12

- ^ "Palestinian leader killed by Israeli rockets". The Telegraph. 27 August 2001.

- ^ "Middle East: Israel and the Occupied Territories and the Palestinian Authority: Without distinction – attacks on civilians by Palestinian armed groups". Amnesty International (Index Number: MDE 02/003/2002). 10 July 2002. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ "Jerusalem synagogue attack: Popular Front for Liberation of Palestine claims responsibility". The Independent. 19 November 2014.

- ^ "Israel Shaken by 5 Deaths in Synagogue Assault", The New York Times

- ^ "Jerusalem synagogue axe attack kills five". Telegraph. 18 November 2014. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ "PFLP Claims Responsibility for Jerusalem synagogue attack" Archived 8 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Hindu

- ^ Chaim Levinson and Gili Cohen (30 June 2015). "Four wounded, one seriously, in West Bank shooting attack". Haaretz. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ "Israeli man wounded in West Bank terror shooting dies in Jerusalem hospital". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ "Netherlands admits to paying terrorists who killed 17-year-old Israeli". The Jerusalem Post | Jpost.com. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ JTA and TOI staff. "Netherlands suspends aid to group that employed suspected Palestinian terrorists". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ Gross, Judah Ari. "Spanish-Palestinian woman pleads guilty to raising PFLP funds through charity". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "صادر عن كتائب الشهيد أبو علي مصطفى الجناح العسكري للجبهة الشعبية لتحرير فلسطين". الجبهة الشعبية لتحرير فلسطين. 7 October 2023. Archived from the original on 8 October 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2023.

- ^ Justin Salhani (30 September 2024). "Israel's attack on Beirut's Kola: What happened and why it matters". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 1 October 2024.

- ^ Homayoun Barkhor (30 September 2024). "PFLP announces assassination of leaders in Israeli airstrike on Beirut". Iranian Students' News Agency (ISNA). Retrieved 1 October 2024.

External links

- PFLP documents at the Marxists Internet Archive

- The Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – PFLP 1967-present Article at the Interactive Encyclopedia of the Palestine Question

- Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine

- 1967 establishments in the Israeli Military Governorate

- Political parties established in 1967

- Anti-Israeli sentiment in Palestine

- Anti-Zionism in the Palestinian territories

- Anti-Zionist political parties

- Arab nationalism in the Palestinian territories

- Arab nationalist militant groups

- Arab nationalist political parties

- Communist terrorism

- Guerrilla organizations

- Marxist parties

- National liberation movements

- Palestinian militant groups

- Resistance movements

- Axis of Resistance

- Socialism in the Palestinian territories

- Organisations designated as terrorist by Japan

- Organizations designated as terrorist by Canada