TOP500

| TOP500 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Key people |

|

| Established | 24 June 1993 |

| Website | top500.org |

The TOP500 project ranks and details the 500 most powerful non-distributed computer systems in the world. The project was started in 1993 and publishes an updated list of the supercomputers twice a year. The first of these updates always coincides with the International Supercomputing Conference in June, and the second is presented at the ACM/IEEE Supercomputing Conference in November. The project aims to provide a reliable basis for tracking and detecting trends in high-performance computing and bases rankings on HPL benchmarks,[1] a portable implementation of the high-performance LINPACK benchmark written in Fortran for distributed-memory computers.

The most recent edition of TOP500 was published in November 2024 as the 64th edition of TOP500, while the next edition of TOP500 will be published in June 2025 as the 65th edition of TOP500. As of November 2024, the United States' El Capitan is the most powerful supercomputer in the TOP500, reaching 1742 petaFlops (1.742 exaFlops) on the LINPACK benchmarks.[2] As of 2018, the United States has by far the highest share of total computing power on the list (nearly 50%).[3] As of 2024, the United States has the highest number of systems with 173 supercomputers; China is in second place with 63, and Germany is third at 40.

The 59th edition of TOP500, published in June 2022, was the first edition of TOP500 to feature only 64-bit supercomputers; as of June 2022, 32-bit supercomputers are no longer listed.[citation needed] The TOP500 list is compiled by Jack Dongarra of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Erich Strohmaier and Horst Simon of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL), and, until his death in 2014, Hans Meuer of the University of Mannheim, Germany.[citation needed] The TOP500 project also includes lists such as Green500 (measuring energy efficiency) and HPCG (measuring I/O bandwidth).[citation needed]

History

[edit]

In the early 1990s, a new definition of supercomputer was needed to produce meaningful statistics. After experimenting with metrics based on processor count in 1992, the idea arose at the University of Mannheim to use a detailed listing of installed systems as the basis. In early 1993, Jack Dongarra was persuaded to join the project with his LINPACK benchmarks. A first test version was produced in May 1993, partly based on data available on the Internet, including the following sources:[4][5]

- "List of the World's Most Powerful Computing Sites" maintained by Gunter Ahrendt[6]

- David Kahaner, the director of the Asian Technology Information Program (ATIP);[7] published a report in 1992, titled "Kahaner Report on Supercomputer in Japan"[5] which had an immense amount of data.[citation needed]

The information from those sources was used for the first two lists. Since June 1993, the TOP500 is produced bi-annually based on site and vendor submissions only. Since 1993, performance of the No. 1 ranked position has grown steadily in accordance with Moore's law, doubling roughly every 14 months. In June 2018, Summit was fastest with an Rpeak[8] of 187.6593 PFLOPS. For comparison, this is over 1,432,513 times faster than the Connection Machine CM-5/1024 (1,024 cores), which was the fastest system in November 1993 (twenty-five years prior) with an Rpeak of 131.0 GFLOPS.[9]

Architecture and operating systems

[edit]

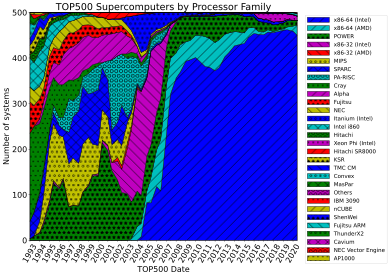

As of June 2022[update], all supercomputers on TOP500 are 64-bit supercomputers, mostly based on CPUs with the x86-64 instruction set architecture, 384 of which are Intel EMT64-based and 101 of which are AMD AMD64-based, with the latter including the top eight supercomputers. 15 other supercomputers are all based on RISC architectures, including six based on ARM64 and seven based on the Power ISA used by IBM Power microprocessors.[citation needed]

In recent years, heterogeneous computing has dominated the TOP500, mostly using Nvidia's graphics processing units (GPUs) or Intel's x86-based Xeon Phi as coprocessors. This is because of better performance per watt ratios and higher absolute performance. AMD GPUs have taken the top 1 and displaced Nvidia in top 10 part of the list. The recent exceptions include the aforementioned Fugaku, Sunway TaihuLight, and K computer. Tianhe-2A is also an interesting exception, as US sanctions prevented use of Xeon Phi; instead, it was upgraded to use the Chinese-designed Matrix-2000[10] accelerators.[citation needed]

Two computers which first appeared on the list in 2018 were based on architectures new to the TOP500. One was a new x86-64 microarchitecture from Chinese manufacturer Sugon, using Hygon Dhyana CPUs (these resulted from a collaboration with AMD, and are a minor variant of Zen-based AMD EPYC) and was ranked 38th, now 117th,[11] and the other was the first ARM-based computer on the list – using Cavium ThunderX2 CPUs.[12] Before the ascendancy of 32-bit x86 and later 64-bit x86-64 in the early 2000s, a variety of RISC processor families made up most TOP500 supercomputers, including SPARC, MIPS, PA-RISC, and Alpha.

All the fastest supercomputers since the Earth Simulator supercomputer have used operating systems based on Linux. Since November 2017[update], all the listed supercomputers use an operating system based on the Linux kernel.[13][14]

Since November 2015, no computer on the list runs Windows (while Microsoft reappeared on the list in 2021 with Ubuntu based on Linux). In November 2014, Windows Azure[15] cloud computer was no longer on the list of fastest supercomputers (its best rank was 165th in 2012), leaving the Shanghai Supercomputer Center's Magic Cube as the only Windows-based supercomputer on the list, until it also dropped off the list. It was ranked 436th in its last appearance on the list released in June 2015, while its best rank was 11th in 2008.[16] There are no longer any Mac OS computers on the list. It had at most five such systems at a time, one more than the Windows systems that came later, while the total performance share for Windows was higher. Their relative performance share of the whole list was however similar, and never high for either. In 2004, the System X supercomputer based on Mac OS X (Xserve, with 2,200 PowerPC 970 processors) once ranked 7th place.[17]

It has been well over a decade since MIPS systems dropped entirely off the list[18] though the Gyoukou supercomputer that jumped to 4th place[19] in November 2017 had a MIPS-based design as a small part of the coprocessors. Use of 2,048-core coprocessors (plus 8× 6-core MIPS, for each, that "no longer require to rely on an external Intel Xeon E5 host processor"[20]) made the supercomputer much more energy efficient than the other top 10 (i.e. it was 5th on Green500 and other such ZettaScaler-2.2-based systems take first three spots).[21] At 19.86 million cores, it was by far the largest system by core-count, with almost double that of the then-best manycore system, the Chinese Sunway TaihuLight.

TOP500

[edit]As of November 2024[update], the number one supercomputer is El Capitan, the leader on Green500 is JEDI, a Bull Sequana XH3000 system using the Nvidia Grace Hopper GH200 Superchip. In June 2022, the top 4 systems of Graph500 used both AMD CPUs and AMD accelerators. After an upgrade, for the 56th TOP500 in November 2020,

Fugaku grew its HPL performance to 442 petaflops, a modest increase from the 416 petaflops the system achieved when it debuted in June 2020. More significantly, the ARMv8.2 based Fugaku increased its performance on the new mixed precision HPC-AI benchmark to 2.0 exaflops, besting its 1.4 exaflops mark recorded six months ago. These represent the first benchmark measurements above one exaflop for any precision on any type of hardware.[22]

Summit, a previously fastest supercomputer, is currently highest-ranked IBM-made supercomputer; with IBM POWER9 CPUs. Sequoia became the last IBM Blue Gene/Q model to drop completely off the list; it had been ranked 10th on the 52nd list (and 1st on the June 2012, 41st list, after an upgrade).

For the first time, all 500 systems deliver a petaflop or more on the High Performance Linpack (HPL) benchmark, with the entry level to the list now at 1.022 petaflops." However, for a different benchmark "Summit and Sierra remain the only two systems to exceed a petaflop on the HPCG benchmark, delivering 2.9 petaflops and 1.8 petaflops, respectively. The average HPCG result on the current list is 213.3 teraflops, a marginal increase from 211.2 six months ago.[23]

Microsoft is back on the TOP500 list with six Microsoft Azure instances (that use/are benchmarked with Ubuntu, so all the supercomputers are still Linux-based), with CPUs and GPUs from same vendors, the fastest one currently 11th,[24] and another older/slower previously made 10th.[25] And Amazon with one AWS instance currently ranked 64th (it was previously ranked 40th). The number of Arm-based supercomputers is 6; currently all Arm-based supercomputers use the same Fujitsu CPU as in the number 2 system, with the next one previously ranked 13th, now 25th.[26]

| Rank (previous) | Rmax Rpeak (PetaFLOPS) |

Name | Model | CPU cores | Accelerator (e.g. GPU) cores | Total Cores (CPUs + Accelerators) | Interconnect | Manufacturer | Site country |

Year | Operating system |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

1,742.00 2,746.38 |

El Capitan | HPE Cray EX255a | 1,051,392 (43,808 × 24-core Optimized 4th Generation EPYC 24C @1.8 GHz) |

9,988,224 (43,808 × 228 AMD Instinct MI300A) |

11,039,616 | Slingshot-11 | HPE | Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory |

2024 | Linux (TOSS) |

| 2 |

1,353.00 2,055.72 |

Frontier | HPE Cray EX235a | 614,656 (9,604 × 64-core Optimized 3rd Generation EPYC 64C @2.0 GHz) |

8,451,520 (38,416 × 220 AMD Instinct MI250X) |

9,066,176 | Slingshot-11 | HPE | Oak Ridge National Laboratory |

2022 | Linux (HPE Cray OS) |

| 3 |

1,012.00 1,980.01 |

Aurora | HPE Cray EX | 1,104,896 (21,248 × 52-core Intel Xeon Max 9470 @2.4 GHz) |

8,159,232 (63,744 × 128 Intel Max 1550) |

9,264,128 | Slingshot-11 | HPE | Argonne National Laboratory |

2023 | Linux (SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 15 SP4) |

| 4 |

561.20 846.84 |

Eagle | Microsoft NDv5 | 172,800 (3,600 × 48-core Intel Xeon Platinum 8480C @2.0 GHz) |

1,900,800 (14,400 × 132 Nvidia Hopper H100) |

2,073,600 | NVIDIA Infiniband NDR | Microsoft | Microsoft |

2023 | Linux (Ubuntu 22.04 LTS) |

| 5 |

477.90 606.97 |

HPC6 | HPE Cray EX235a | 213,120 (3,330 × 64-core Optimized 3rd Generation EPYC 64C @2.0 GHz) |

2,930,400 (13,320 × 220 AMD Instinct MI250X) |

3,143,520 | Slingshot-11 | HPE | Eni S.p.A |

2024 | Linux (RHEL 8.9) |

| 6 |

442.01 537.21 |

Fugaku | Supercomputer Fugaku | 7,630,848 (158,976 × 48-core Fujitsu A64FX @2.2 GHz) |

- | 7,630,848 | Tofu interconnect D | Fujitsu | Riken Center for Computational Science |

2020 | Linux (RHEL) |

| 7 |

434.90 574.84 |

Alps | HPE Cray EX254n | 748,800 (10,400 × 72-Arm Neoverse V2 cores Nvidia Grace @3.1 GHz) |

1,372,800 (10,400 × 132 Nvidia Hopper H100) |

2,121,600 | Slingshot-11 | HPE | CSCS Swiss National Supercomputing Centre |

2024 | Linux (HPE Cray OS) |

| 8 |

379.70 531.51 |

LUMI | HPE Cray EX235a | 186,624 (2,916 × 64-core Optimized 3rd Generation EPYC 64C @2.0 GHz) |

2,566,080 (11,664 × 220 AMD Instinct MI250X) |

2,752,704 | Slingshot-11 | HPE | EuroHPC JU |

2022 | Linux (HPE Cray OS) |

| 9 |

241.20 306.31 |

Leonardo | BullSequana XH2000 | 110,592 (3,456 × 32-core Xeon Platinum 8358 @2.6 GHz) |

1,714,176 (15,872 × 108 Nvidia Ampere A100) |

1,824,768 | Quad-rail NVIDIA HDR100 Infiniband | Atos | EuroHPC JU |

2023 | Linux (RHEL 8)[28] |

| 10 |

208.10 288.88 |

Tuolumne | HPE Cray EX255a | 110,592 (4,608 × 24-core Optimized 4th Generation EPYC 24C @1.8 GHz) |

1,050,624 (4,608 × 228 AMD Instinct MI300A) |

1,161,216 | Slingshot-11 | HPE | Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory |

2024 | Linux (TOSS) |

Legend:[29]

- Rank – Position within the TOP500 ranking. In the TOP500 list table, the computers are ordered first by their Rmax value. In the case of equal performances (Rmax value) for different computers, the order is by Rpeak. For sites that have the same computer, the order is by memory size and then alphabetically.

- Rmax – The highest score measured using the LINPACK benchmarks suite. This is the number that is used to rank the computers. Measured in quadrillions of 64-bit floating point operations per second, i.e., petaFLOPS.[30]

- Rpeak – This is the theoretical peak performance of the system. Computed in petaFLOPS.

- Name – Some supercomputers are unique, at least on its location, and are thus named by their owner.

- Model – The computing platform as it is marketed.

- Processor – The instruction set architecture or processor microarchitecture, alongside GPU and accelerators when available.

- Interconnect – The interconnect between computing nodes. InfiniBand is most used (38%) by performance share, while Gigabit Ethernet is most used (54%) by number of computers.

- Manufacturer – The manufacturer of the platform and hardware.

- Site – The name of the facility operating the supercomputer.

- Country – The country in which the computer is located.

- Year – The year of installation or last major update.

- Operating system – The operating system that the computer uses.

Other rankings

[edit]Top countries

[edit]Numbers below represent the number of computers in the TOP500 that are in each of the listed countries or territories. As of 2024, United States has the most supercomputers on the list, with 173 machines. The United States has the highest aggregate computational power at 6,324 Petaflops Rmax with Japan second (919 Pflop/s) and Germany third (396 Pflop/s).

| Country or Territory | Systems |

|---|---|

| Country/Region | Nov 2024[32] | Jun 2024[33] | Nov 2023[34] | Jun 2023[35] | Nov 2022[36] | Jun 2022[37] | Nov 2021[38] | Jun 2021[39] | Nov 2020[40] | Jun 2020[41] | Nov 2019[42] | Jun 2019[43] | Nov 2018[44] | Jun 2018[45] | Nov 2017[46] | Jun 2017[47] | Nov 2016[48] | Jun 2016[49] | Nov 2015[50] | Jun 2015[51] | Nov 2014[52] | Jun 2014[53] | Nov 2013[54] | Jun 2013[55] | Nov 2012[56] | Jun 2012[57] | Nov 2011[58] | Jun 2011[59] | Nov 2010[60] | Jun 2010[61] | Nov 2009[62] | Jun 2009[63] | Nov 2008[64] | Jun 2008[65] | Nov 2007[66] | Jun 2007[67] | Nov 2006[68] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 173 | 171 | 161 | 150 | 127 | 128 | 149 | 122 | 113 | 114 | 117 | 116 | 109 | 124 | 143 | 168 | 171 | 165 | 199 | 233 | 231 | 232 | 264 | 252 | 251 | 252 | 263 | 255 | 274 | 282 | 277 | 291 | 290 | 257 | 283 | 281 | 309 | |

| 129 | 123 | 112 | 103 | 101 | 92 | 83 | 93 | 79 | 79 | 87 | 92 | 91 | 93 | 86 | 99 | 95 | 93 | 94 | 122 | 110 | 103 | 89 | 97 | 89 | 96 | 95 | 109 | 108 | 126 | 137 | 134 | 140 | 169 | 133 | 115 | 82 | |

| 63 | 80 | 104 | 134 | 162 | 173 | 173 | 188 | 214 | 226 | 228 | 220 | 227 | 206 | 202 | 160 | 171 | 168 | 109 | 37 | 61 | 76 | 63 | 66 | 72 | 68 | 74 | 61 | 41 | 24 | 21 | 21 | 15 | 12 | 10 | 13 | 18 | |

| 40 | 40 | 36 | 36 | 34 | 31 | 26 | 23 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 13 | 17 | 21 | 21 | 28 | 31 | 26 | 33 | 37 | 26 | 22 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 26 | 24 | 27 | 29 | 25 | 46 | 31 | 24 | 18 | |

| 34 | 29 | 32 | 33 | 31 | 33 | 32 | 34 | 34 | 29 | 29 | 28 | 31 | 36 | 35 | 33 | 27 | 29 | 37 | 40 | 32 | 30 | 28 | 30 | 32 | 35 | 30 | 26 | 26 | 18 | 16 | 15 | 17 | 22 | 20 | 23 | 30 | |

| 24 | 24 | 23 | 24 | 24 | 22 | 19 | 16 | 18 | 19 | 18 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 27 | 30 | 27 | 22 | 23 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 26 | 23 | 26 | 34 | 17 | 13 | 12 | |

| 14 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 11 | 18 | 20 | 22 | 15 | 17 | 13 | 11 | 18 | 29 | 30 | 30 | 23 | 29 | 24 | 25 | 27 | 27 | 25 | 38 | 45 | 44 | 46 | 53 | 48 | 42 | 30 | |

| 14 | 11 | 12 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 8 | |

| 13 | 13 | 12 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 6 | |

| 10 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 6 | 11 | 16 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 2 | |

| 9 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | |

| 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 14 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 10 | 8 | |

| 8 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 10 | 1 | |

| 8 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 10 | 2 | |

| 7 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | |

| 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 11 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 10 | |

| 6 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 2 | |

| 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | |

| 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 5 | |

| 4 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | |

| 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 7 | |

| 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Fastest supercomputer in TOP500 by country

[edit](As of November 2023[69])

| Country/Territory | Fastest supercomputer of country/territory (name) | Rank in TOP500 | Rmax Rpeak (TFlop/s) |

Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Capitan | 1 | 1,742,000.0 2,746,380.0 |

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory | |

| Fugaku | 4 | 442,010.0 537,210.0 |

RIKEN | |

| LUMI | 5 | 379,700.0 531,510.0 |

Center for Scientific Computing | |

| Leonardo | 6 | 238,700.0 304,470.0 |

CINECA | |

| MareNostrum | 8 | 138,200.0 265,570.0 |

Barcelona Supercomputing Center | |

| Sunway TaihuLight | 11 | 93,010.0 125,440.0 |

National Supercomputing Center, Wuxi | |

| ISEG | 16 | 46,540.0 86,790.0 |

Nebius | |

| Adastra | 17 | 46,100.0 61,610.0 |

GENCI-CINES | |

| JUWELS (booster module) | 18 | 44,120.0 70,980.0 |

Forschungszentrum Jülich | |

| Shaheen III | 20 | 35,660.0 39,610.0 |

King Abdullah University of Science and Technology | |

| Sejong | 22 | 32,970.0 40,770.0 |

Naver Corporation | |

| Setonix | 25 | 27,160.0 35,000.0 |

Pawsey Supercomputing Centre | |

| DeepL Mercury | 34 | 21,850.0 33,850.0 |

DeepL SE | |

| Chervonenkis | 36 | 21,530.0 29,420.0 |

Yandex | |

| Piz Daint | 37 | 21,230.0 27,150.0 |

Swiss National Supercomputing Centre | |

| ARCHER2 | 39 | 19,540.0 25,800.0 |

EPSRC/University of Edinburgh | |

| Pégaso | 45 | 19,070.0 42,000.0 |

Petróleo Brasileiro S.A | |

| PRIMEHPC FX1000 | 69 | 11,160.0 12,980.0 |

Central Weather Administration | |

| MeluXina - Accelerator Module | 71 | 10,520.0 15,290.0 |

LuxProvide | |

| Airawat | 90 | 8,500.0 13,170.0 |

Centre for Development of Advanced Computing | |

| Lanta | 94 | 8,150.0 13,770.0 |

NECTEC | |

| Underhill | 102 | 7,760.0 10,920.0 |

Shared Services Canada | |

| Artemis | 107 | 7,260.0 9,490.0 |

Group 42 | |

| Karolina, GPU partition | 113 | 6,750.0 9,080.0 |

IT4Innovations National Supercomputing Center, VSB-Technical University of Ostrava | |

| Athena | 155 | 5,050.0 7,710.0 |

AGH University of Science and Technology | |

| Betzy | 161 | 4,720.0 6,190.0 |

UNINETT Sigma2 AS | |

| Discoverer | 166 | 4,520.0 5,940.0 |

Consortium Petascale Supercomputer Bulgaria | |

| Clementina XXI | 196 | 3,880.0 5,990.0 |

Servicio Meteorológico Nacional | |

| VEGA HPC CPU | 198 | 3,820.0 5,370.0 |

IZUM | |

| AIC1 | 218 | 3,550.0 6,970.0 |

Software Company MIR | |

| Aspire 2A | 233 | 3,330.0 6,480.0 |

National Supercomputing Centre Singapore | |

| Toubkal | 246 | 3,160.0 5,010.0 |

Mohammed VI Polytechnic University - African Supercomputing Centre | |

| Komondor | 266 | 3,100.0 4,510.0 |

Governmental Information Technology Development Agency (KIFÜ) | |

| VSC-4 | 319 | 2,730.0 3,760.0 |

Vienna Scientific Cluster | |

| Lucia | 322 | 2,720.0 5,310.0 |

Cenaero |

Systems ranked No. 1

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2019) |

- HPE Cray El Capitan (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

United States, November 2024 – Present)[70]

United States, November 2024 – Present)[70] - HPE Cray Frontier (Oak Ridge National Laboratory

United States, June 2022 – November 2024)[71]

United States, June 2022 – November 2024)[71] - Supercomputer Fugaku (Riken Center for Computational Science

Japan, June 2020 – June 2022)[72]

Japan, June 2020 – June 2022)[72] - IBM Summit (Oak Ridge National Laboratory

United States, June 2018 – June 2020)[73]

United States, June 2018 – June 2020)[73] - NRCPC Sunway TaihuLight (National Supercomputing Center in Wuxi

China, June 2016 – November 2017)

China, June 2016 – November 2017) - NUDT Tianhe-2A (National Supercomputing Center of Guangzhou

China, June 2013 – June 2016)

China, June 2013 – June 2016) - Cray Titan (Oak Ridge National Laboratory

United States, November 2012 – June 2013)[74]

United States, November 2012 – June 2013)[74] - IBM Sequoia Blue Gene/Q (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

United States, June 2012 – November 2012)[75]

United States, June 2012 – November 2012)[75] - Fujitsu K computer (Riken Advanced Institute for Computational Science

Japan, June 2011 – June 2012)

Japan, June 2011 – June 2012) - NUDT Tianhe-1A (National Supercomputing Center of Tianjin

China, November 2010 – June 2011)

China, November 2010 – June 2011) - Cray Jaguar (Oak Ridge National Laboratory

United States, November 2009 – November 2010)

United States, November 2009 – November 2010) - IBM Roadrunner (Los Alamos National Laboratory

United States, June 2008 – November 2009)

United States, June 2008 – November 2009) - IBM Blue Gene/L (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

United States, November 2004 – June 2008)[76]

United States, November 2004 – June 2008)[76] - NEC Earth Simulator (Earth Simulator Center

Japan, June 2002 – November 2004)

Japan, June 2002 – November 2004) - IBM ASCI White (Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

United States, November 2000 – June 2002)

United States, November 2000 – June 2002) - Intel ASCI Red (Sandia National Laboratories

United States, June 1997 – November 2000)[77]

United States, June 1997 – November 2000)[77] - Hitachi CP-PACS (University of Tsukuba

Japan, November 1996 – June 1997)

Japan, November 1996 – June 1997) - Hitachi SR2201 (University of Tokyo

Japan, June 1996 – November 1996)

Japan, June 1996 – November 1996) - Fujitsu Numerical Wind Tunnel (National Aerospace Laboratory of Japan

Japan, November 1994 – June 1996)

Japan, November 1994 – June 1996) - Intel Paragon XP/S140 (Sandia National Laboratories

United States, June 1994 – November 1994)

United States, June 1994 – November 1994) - Fujitsu Numerical Wind Tunnel (National Aerospace Laboratory of Japan

Japan, November 1993 – June 1994)

Japan, November 1993 – June 1994) - TMC CM-5 (Los Alamos National Laboratory

United States, June 1993 – November 1993)

United States, June 1993 – November 1993)

Additional statistics

[edit]By number of systems as of November 2024[update]:[78]

| Accelerator | Systems |

|---|---|

| NVIDIA AMPERE A100 (Launched: 2020) | |

| NVIDIA TESLA V100 (Launched: 2017) | |

| NVIDIA AMPERE A100 SXM4 40 GB (Launched: 2020) | |

| NVIDIA HOPPER H100 (Launched: 2022) | |

| NVIDIA HOPPER H100 SXM5 80 GB (Launched: 2022) |

| Manufacturer | Systems |

|---|---|

| Lenovo | |

| Hewlett Packard Enterprise | |

| EVIDEN | |

| DELL | |

| Nvidia |

| Operating System | Systems |

|---|---|

| Linux | |

| CentOS | |

| HPE Cray OS | |

| Red Hat Enterprise Linux | |

| Cray Linux Environment |

Note: All operating systems of the TOP500 systems are Linux-family based, but Linux above is generic Linux.

Sunway TaihuLight is the system with the most CPU cores (10,649,600). Tianhe-2 has the most GPU/accelerator cores (4,554,752). Aurora is the system with the greatest power consumption with 38,698 kilowatts.

New developments in supercomputing

[edit]In November 2014, it was announced that the United States was developing two new supercomputers to exceed China's Tianhe-2 in its place as world's fastest supercomputer. The two computers, Sierra and Summit, will each exceed Tianhe-2's 55 peak petaflops. Summit, the more powerful of the two, will deliver 150–300 peak petaflops.[79] On 10 April 2015, US government agencies banned selling chips, from Nvidia to supercomputing centers in China as "acting contrary to the national security ... interests of the United States";[80] and Intel Corporation from providing Xeon chips to China due to their use, according to the US, in researching nuclear weapons – research to which US export control law bans US companies from contributing – "The Department of Commerce refused, saying it was concerned about nuclear research being done with the machine."[81]

On 29 July 2015, President Obama signed an executive order creating a National Strategic Computing Initiative calling for the accelerated development of an exascale (1000 petaflop) system and funding research into post-semiconductor computing.[82]

In June 2016, Japanese firm Fujitsu announced at the International Supercomputing Conference that its future exascale supercomputer will feature processors of its own design that implement the ARMv8 architecture. The Flagship2020 program, by Fujitsu for RIKEN plans to break the exaflops barrier by 2020 through the Fugaku supercomputer, (and "it looks like China and France have a chance to do so and that the United States is content – for the moment at least – to wait until 2023 to break through the exaflops barrier."[83]) These processors will also implement extensions to the ARMv8 architecture equivalent to HPC-ACE2 that Fujitsu is developing with Arm.[83]

In June 2016, Sunway TaihuLight became the No. 1 system with 93 petaflop/s (PFLOP/s) on the Linpack benchmark.[84]

In November 2016, Piz Daint was upgraded, moving it from 8th to 3rd, leaving the US with no systems under the TOP3 for the 2nd time.[85][86]

Inspur, based out of Jinan, China, is one of the largest HPC system manufacturers. As of May 2017[update], Inspur has become the third manufacturer to have manufactured a 64-way system – a record that has previously been held by IBM and HP. The company has registered over $10B in revenue and has provided a number of systems to countries such as Sudan, Zimbabwe, Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. Inspur was also a major technology partner behind both the Tianhe-2 and Taihu supercomputers, occupying the top 2 positions of the TOP500 list up until November 2017. Inspur and Supermicro released a few platforms aimed at HPC using GPU such as SR-AI and AGX-2 in May 2017.[87]

In June 2018, Summit, an IBM-built system at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) in Tennessee, US, took the No. 1 spot with a performance of 122.3 petaflop/s (PFLOP/s), and Sierra, a very similar system at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, CA, US took #3. These systems also took the first two spots on the HPCG benchmark. Due to Summit and Sierra, the US took back the lead as consumer of HPC performance with 38.2% of the overall installed performance while China was second with 29.1% of the overall installed performance. For the first time ever, the leading HPC manufacturer was not a US company. Lenovo took the lead with 23.8% of systems installed. It is followed by HPE with 15.8%, Inspur with 13.6%, Cray with 11.2%, and Sugon with 11%. [88]

On 18 March 2019, the United States Department of Energy and Intel announced the first exaFLOP supercomputer would be operational at Argonne National Laboratory by the end of 2021. The computer, named Aurora, was delivered to Argonne by Intel and Cray.[89][90]

On 7 May 2019, The U.S. Department of Energy announced a contract with Cray to build the "Frontier" supercomputer at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Frontier is anticipated to be operational in 2021 and, with a performance of greater than 1.5 exaflops, should then be the world's most powerful computer.[91]

Since June 2019, all TOP500 systems deliver a petaflop or more on the High Performance Linpack (HPL) benchmark, with the entry level to the list now at 1.022 petaflops.[92]

In May 2022, the Frontier supercomputer broke the exascale barrier, completing more than a quintillion 64-bit floating point arithmetic calculations per second. Frontier clocked in at approximately 1.1 exaflops, beating out the previous record-holder, Fugaku.[93][94]

Large machines not on the list

[edit]Some major systems are not on the list. A prominent example is the NCSA's Blue Waters which publicly announced the decision not to participate in the list[95] because they do not feel it accurately indicates the ability of any system to do useful work.[96] Other organizations decide not to list systems for security and/or commercial competitiveness reasons. One such example is the National Supercomputing Center at Qingdao's OceanLight supercomputer, completed in March 2021, which was submitted for, and won, the Gordon Bell Prize. The computer is an exaflop computer, but was not submitted to the TOP500 list; the first exaflop machine submitted to the TOP500 list was Frontier. Analysts suspected that the reason the NSCQ did not submit what would otherwise have been the world's first exascale supercomputer was to avoid inflaming political sentiments and fears within the United States, in the context of the United States – China trade war.[97] Additional purpose-built machines that are not capable or do not run the benchmark were not included, such as RIKEN MDGRAPE-3 and MDGRAPE-4.

A Google Tensor Processing Unit v4 pod is capable of 1.1 exaflops of peak performance,[98] while TPU v5p claims over 4 exaflops in Bfloat16 floating-point format,[99] however these units are highly specialized to run machine learning workloads and the TOP500 measures a specific benchmark algorithm using a specific numeric precision.

In March 2024, Meta AI disclosed the operation of two datacenters with 24,576 H100 GPUs,[100] which is almost 2x as on the Microsoft Azure Eagle (#3 as of September 2024), which could have made them occupy 3rd and 4th places in TOP500, but neither have been benchmarked. During company's Q3 2024 earnings call in October, M. Zuckerberg disclosed usage of a cluster with over 100,000 H100s.[101]

xAI Memphis Supercluster (also known as "Colossus") allegedly features 100,000 of the same H100 GPUs, which could have put in on the first place, but it is reportedly not in full operation due to power shortages.[102]

Computers and architectures that have dropped off the list

[edit]IBM Roadrunner[103] is no longer on the list (nor is any other using the Cell coprocessor, or PowerXCell).

Although Itanium-based systems reached second rank in 2004,[104][105] none now remain.

Similarly (non-SIMD-style) vector processors (NEC-based such as the Earth simulator that was fastest in 2002[106]) have also fallen off the list. Also the Sun Starfire computers that occupied many spots in the past now no longer appear.

The last non-Linux computers on the list – the two AIX ones – running on POWER7 (in July 2017 ranked 494th and 495th,[107] originally 86th and 85th), dropped off the list in November 2017.

Notes

[edit]- The first edition of TOP500 to feature only 64-bit supercomputers was the 59th edition of TOP500, which was published in June 2022.

- As of June 2022, TOP500 features only 64-bit supercomputers.

- The world’s most powerful supercomputers are from the United States and Japan.

See also

[edit]- Computer science

- Computing

- Graph500

- Green500

- HPC Challenge Benchmark

- Instructions per second

- LINPACK benchmarks

- List of fastest computers

References

[edit]- ^ A. Petitet; R. C. Whaley; J. Dongarra; A. Cleary (24 February 2016). "HPL – A Portable Implementation of the High-Performance Linpack Benchmark for Distributed-Memory Computers". ICL – UTK Computer Science Department. Archived from the original on 2 November 2000. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ "November 2024 | TOP500". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 18 November 2024. Retrieved 19 November 2024.

- ^ "List Statistics | TOP500". Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "An Interview with Jack Dongarra by Alan Beck, editor in chief HPCwire". Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ a b "Statistics on Manufacturers and Continents". Archived from the original on 18 September 2007. Retrieved 10 March 2007.

- ^ "The TOP25 Supercomputer Sites". Archived from the original on 23 January 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Where does Asia stand? This rising supercomputing power is reaching for real-world HPC leadership". Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Rpeak – This is the theoretical peak performance of the system. Measured in PetaFLOPS.

- ^ "Sublist Generator". Archived from the original on 27 August 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ "Matrix-2000 - NUDT". WikiChip. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ "Advanced Computing System(PreE) - Sugon TC8600, Hygon Dhyana 32C 2GHz, Deep Computing Processor, 200Gb 6D-Torus | TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Astra - Apollo 70, Cavium ThunderX2 CN9975-2000 28C 2GHz, 4xEDR Infiniband | TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Top500 – List Statistics". www.top500.org. November 2017. Archived from the original on 19 November 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ^ "Linux Runs All of the World's Fastest Supercomputers". The Linux Foundation. 20 November 2017. Archived from the original on 26 November 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2020.

- ^ "Microsoft Windows Azure". Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "Magic Cube – Dawning 5000A, QC Opteron 1.9 GHz, Infiniband, Windows HPC 2008". Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "System X - 1100 Dual 2.3 GHz Apple XServe/Mellanox Infiniband 4X/Cisco GigE | TOP500". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ "Origin 2000 195/250 MHz". Top500. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ "Gyoukou - ZettaScaler-2.2 HPC system, Xeon D-1571 16C 1.3 GHz, Infiniband EDR, PEZY-SC2 700 MHz". Top 500. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ "PEZY-SC2 - PEZY". Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ "The 2,048-core PEZY-SC2 sets a Green500 record". WikiChip Fuse. 1 November 2017. Archived from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

Powering the ZettaScaler-2.2 is the PEZY-SC2. The SC2 is a second-generation chip featuring twice as many cores – i.e., 2,048 cores with 8-way SMT for a total of 16,384 threads. […] The first-generation SC incorporated two ARM926 cores and while that was sufficient for basic management and debugging its processing power was inadequate for much more. The SC2 uses a hexa-core P-Class P6600 MIPS processor which share the same memory address as the PEZY cores, improving performance and reducing data transfer overhead. With the powerful MIPS management cores, it is now also possible to entirely eliminate the Xeon host processor. However, PEZY has not done so yet.

- ^ "November 2020 | TOP500". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 21 November 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Becomes a Petaflop Club for Supercomputers | TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ "Explorer-WUS3 - ND96_amsr_MI200_v4, AMD EPYC 7V12 48C 2.45GHz, AMD Instinct MI250X, Infiniband HDR | TOP500". www.top500.org. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ "Voyager-EUS2". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 5 April 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ "Wisteria/BDEC-01 (Odyssey) - PRIMEHPC FX1000, A64FX 48C 2.2GHz, Tofu interconnect D | TOP500". www.top500.org. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ "November 2024 | TOP500". www.top500.org. Retrieved 18 November 2024.

- ^ Turisini, Matteo; Cestari, Mirko; Amati, Giorgio (15 January 2024). "LEONARDO: A Pan-European Pre-Exascale Supercomputer for HPC and AI applications". Journal of Large-scale Research Facilities JLSRF. 9 (1). doi:10.17815/jlsrf-8-186. ISSN 2364-091X.

- ^ "TOP500 DESCRIPTION". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 23 June 2020. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ "FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 3 April 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- ^ "LIST STATISTICS". Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2024.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2024. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 18 November 2024.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2024. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 3 June 2024.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2023. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2023. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2022. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2022. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2021. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2021. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2020. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2020. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2019. Archived from the original on 19 November 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2019. Archived from the original on 4 October 2019. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2018. Archived from the original on 12 June 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2018. Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2017. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2017. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2016. Archived from the original on 3 December 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2016. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2015. Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2015. Archived from the original on 28 August 2019. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2014. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2014. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2013. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2013. Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2012. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2012. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2011. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2011. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2010. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2010. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2009. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2009. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2008. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". June 2008. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2007. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2007. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". November 2007. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". 13 November 2023. Archived from the original on 13 November 2023. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ "November 2024 | TOP500". top500.org. Retrieved 19 November 2024.

- ^ "TOP500 List - November 2023". November 2023. Archived from the original on 1 March 2024. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "June 2020". June 2020. Archived from the original on 1 September 2022. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ Summit, an IBM-built supercomputer now running at the Department of Energy's (DOE) Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL), captured the number one spot June 2018 with a performance of 122.3 petaflops on High Performance Linpack (HPL), the benchmark used to rank the TOP500 list. Summit has 4,356 nodes, each one equipped with two 22-core POWER9 CPUs, and six NVIDIA Tesla V100 GPUs. The nodes are linked together with a Mellanox dual-rail EDR InfiniBand network."TOP500 List - June 2018". The TOP500 List of the 500 most powerful commercially available computer systems known. The TOP500 project. 30 June 2018. Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ Advanced reports that Oak Ridge National Laboratory was fielding the world's fastest supercomputer were proven correct when the 40th edition of the twice-yearly TOP500 List of the world's top supercomputers was released today (Nov. 12, 2012). Titan, a Cray XK7 system installed at Oak Ridge, achieved 17.59 Petaflop/s (quadrillions of calculations per second) on the Linpack benchmark. Titan has 560,640 processors, including 261,632 NVIDIA K20x accelerator cores."TOP500 List - November 2012". The TOP500 List of the 500 most powerful commercially available computer systems known. The TOP500 project. 12 November 2012. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ For the first time since November 2009, a United States supercomputer sits atop the TOP500 list of the world's top supercomputers. Named Sequoia, the IBM BlueGene/Q system installed at the Department of Energy's Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory achieved an impressive 16.32 petaflop/s on the Linpack benchmark using 1,572,864 cores."TOP500 List - June 2012". The TOP500 List of the 500 most powerful commercially available computer systems known. The TOP500 project. 30 June 2012. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ The DOE/IBM BlueGene/L beta-System was able to claim the No. 1 position on the new TOP500 list with its record Linpack benchmark performance of 70.72 Tflop/s ("teraflops" or trillions of calculations per second). This system, once completed, will be moved to the DOE's Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in Livermore, Calif."TOP500 List - November 2004". The TOP500 List of the 500 most powerful commercially available computer systems known. The TOP500 project. 30 November 2004. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ ASCI Red a Sandia National Laboratories machine with 7264 Intel cores nabbed the #1 position in June of 1997."TOP500 List -June 1997". The TOP500 List of the 500 most powerful commercially available computer systems known. The TOP500 project. 30 June 1997. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- ^ "List Statistics". Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2024.

- ^ Balthasar, Felix. "US Government Funds $425 million to build two new Supercomputers". News Maine. Archived from the original on 19 November 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ "Nuclear worries stop Intel from selling chips to Chinese supercomputers". CNN. 10 April 2015. Archived from the original on 8 December 2018. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ^ "US nuclear fears block Intel China supercomputer update". BBC News. 10 April 2015. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- ^ "Executive Order -- Creating a National Strategic Computing Initiative" (Executive order). The White House – Office of the Press Secretary. 29 July 2015. Archived from the original on 30 November 2018.

- ^ a b Morgan, Timothy Prickett (23 June 2016). "Inside Japan's Future Exascale ARM Supecomputer". The Next Platform. Archived from the original on 27 June 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ^ "Highlights - June 2016 | TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 5 April 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "Highlights - June 2017 | TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "TOP500 List Refreshed, US Edged Out of Third Place | TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "Supermicro, Inspur, Boston Limited Unveil High-Density GPU Servers | TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 13 June 2017.

- ^ "Highlights - June 2018 | TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 5 April 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Department of Energy and Intel to deliver first exascale supercomputer1". Argonne National Laboratory. 18 March 2019. Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- ^ Clark, Don (18 March 2019). "Racing Against China, U.S. Reveals Details of $500 Million Supercomputer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 28 June 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "U.S. Department of Energy and Cray to Deliver Record-Setting Frontier Supercomputer at ORNL". Oak Ridge National Laboratory. 8 May 2019. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ "TOP500 Becomes a Petaflop Club for Supercomputers | TOP500 Supercomputer Sites". www.top500.org. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ Emily Conover (1 June 2022). "The world's fastest supercomputer just broke the exascale barrier". ScienceNews. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ Don Clark (30 May 2022). "U.S. Retakes Top Spot in Supercomputer Race". New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 1 June 2022.

- ^ Blue Waters Opts Out of TOP500 (article), 16 November 2012, archived from the original on 13 December 2019, retrieved 30 June 2016

- ^ Kramer, William, Top500 versus Sustained Performance – Or the Ten Problems with the TOP500 List – And What to Do About Them. 21st International Conference On Parallel Architectures And Compilation Techniques (PACT12), 19–23 September 2012, Minneapolis, MN, US

- ^ "Three Chinese Exascale Systems Detailed at SC21: Two Operational and One Delayed". 24 November 2021. Archived from the original on 2 September 2022. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- ^ Google demonstrates leading performance in latest MLPerf Benchmarks (article), 30 June 2021, archived from the original on 10 July 2021, retrieved 10 July 2021

- ^ "TPU v5p". Google Cloud. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ "Meta has two new AI data centers equipped with over 24,000 NVIDIA H100 GPUs". TweakTown. 13 March 2024. Retrieved 7 September 2024.

- ^ https://finance.yahoo.com/news/meta-platforms-meta-q3-2024-010026926.html

- ^ "Elon Musk's xAI data center 'adding to Memphis air quality problems' - campaign group". 27 August 2024.

- ^ "Roadrunner – BladeCenter QS22/LS21 Cluster, PowerXCell 8i 3.2 GHz / Opteron DC 1.8 GHz, Voltaire Infiniband". Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Thunder – Intel Itanium2 Tiger4 1.4 GHz – Quadrics". Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Columbia – SGI Altix 1.5/1.6/1.66 GHz, Voltaire Infiniband". Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "Japan Agency for Marine -Earth Science and Technology". Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "IBM Flex System p460, POWER7 8C 3.550 GHz, Infiniband QDR". TOP500 Supercomputer Sites. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- LINPACK benchmarks at TOP500